THE SYMPOSIUM BY PLATO

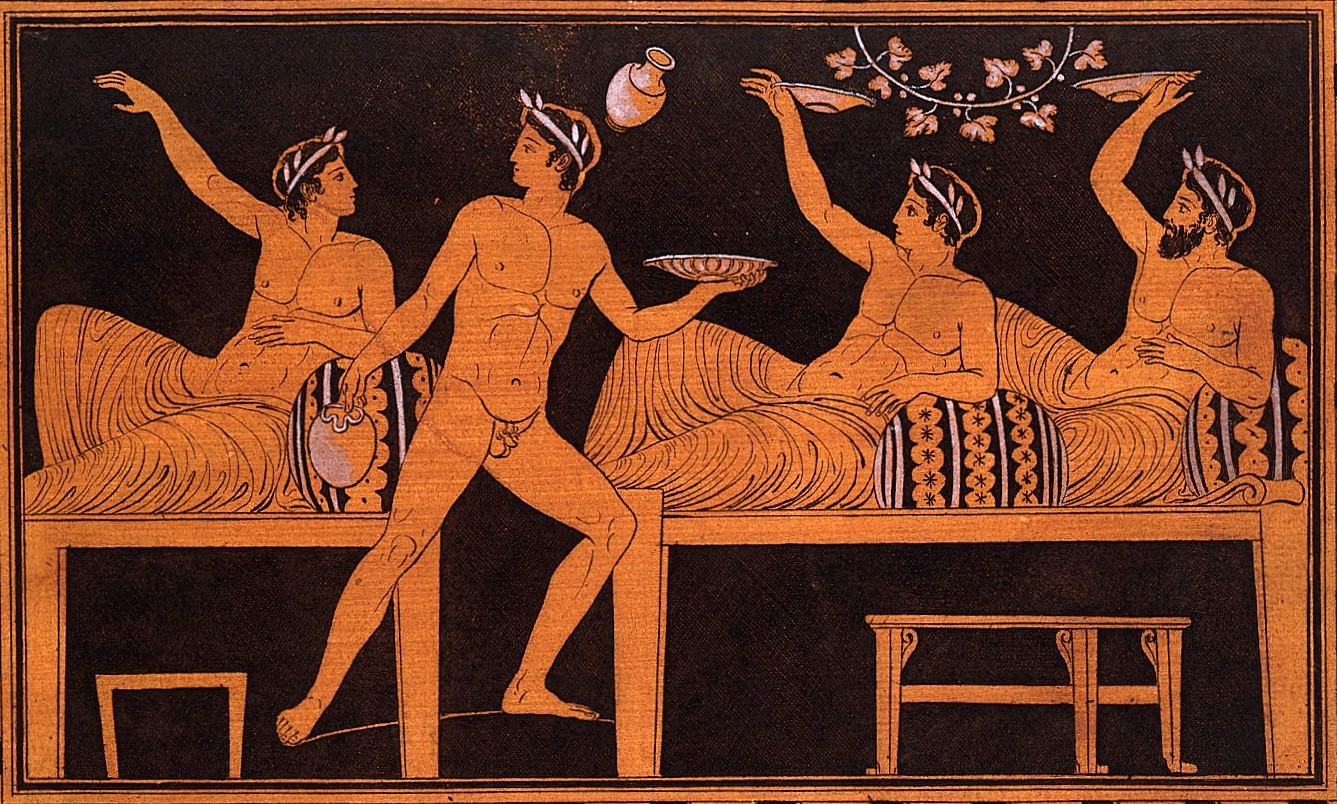

The Symposium, written around 370 BC, is the best-known work by Plato, the pre-eminent philosopher of antiquity. So-called from being discourse over wine after a banquet, it depicts a friendly contest of extemporaneous speeches about Eros, the god of love, between some mostly-famous Athenians.

The setting is a party at the house of the tragedian Agathon, held to celebrate his winning a prize for a play in 416 BC.

Presented here is the approximate half of the work relevant to pederasty. Though the discussion of love is tilted towards pederasty,[1] there are passages irrelevant to it, which either tell the story of the evening, or present abstract ideas about love which have nothing to say about its pederastic form, or simply digress. To provide context and continuity, a brief synopsis is given of these omitted passages.

The translation largely follows that of Benjamin Jowett published by the Oxford University Press in 1892, but has been quite heavily amended. Mostly this has been due to Jowett’s persistent reticence and occasional evasion[2] where the Greek is most clear about the sexual character of the love described, which he doubtless felt unavoidable under his nineteenth-century circumstances.[3] His occasional use of sixteenth-century English and his latinisation of Greek names have also been undone.

In the names of the works of art used for illustrating this article, Eros and his mother Aphrodite have often been better known by their Latin names of Cupid and Venus. These have been used here where they are original to the work of art or firmly established, but the Greek names have been preferred where there has been ambiguity.

| Symposium | Συμπόσιον |

The whole story is told several years after the event[4] by a follower of Sokrates called Apollodoros, who had not been there, having been only a boy then, but had heard the oft-repeated story from one who was, and checked it with another, Sokrates himself. Dinner over, the symposium begins with the physician Eryximachos proposing, and the others agreeing, that each of them should make a speech in praise of Eros, beginning with Phaidros. (172a-178a)

178a-185c

|

As I said, Phaidros[5] began by affirming that Love is a mighty god, and wonderful among gods and men, but especially wonderful in his birth. “For he is the eldest of the gods, which is an honour to him; and a proof of his claim to this honour is, that of his parents there is no memorial; neither poet nor prose-writer has ever affirmed that he had any. As Hesiod says:— First Chaos came, and then broad-bosomed Earth, The everlasting seat of all that is, And Eros.[6] In other words, after Chaos, the Earth and Eros, these two, came into being. Also Parmenides sings of Generation: First in the train of gods, he fashioned Eros. And Akousilaos agrees with Hesiod. So there is widespread agreement that Eros is among the oldest. And being the oldest, he is also the source of the greatest benefits, for I cannot say what greater good there is for a boy than finding a good lover, or for a lover than finding a boy to love. Love, more than anything (more than family, honours or wealth), implants in men the thing which must be their guide if they are to live a good life. And what is that? It is shame of what is shameful, and a passionate desire for what is good, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work. And I say that a man in love who is detected in doing any dishonourable act, or submitting through cowardice when any dishonour is done to him by another, will be more pained at being detected by the boy he loves than at being seen by his father, or by his comrades, or by any one else. And one can see just the same thing happening with the boy. He is more worried about being caught behaving badly by his admirers than by anyone else. And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best managers of their own city, abstaining from all dishonour, and emulating one another in honour; and when fighting at each other's side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.[7] For what lover would not prefer to be seen by all mankind than by his boy when abandoning his post or throwing away his weapons? He would be ready to die many times over rather than endure this. Or who would desert his boy or not come to his aid when he is in danger? The veriest coward would become an inspired hero, equal to the bravest, at such a time; Eros would inspire him. That courage which, as Homer says, the god breathes into the souls of some heroes, Eros imparts to lovers.  “What is more, lovers are the only ones willing to die for others, and that is true not only of men, but of women as well. Of this, Alkestis, the daughter of Pelias, is a monument to all Hellas. She alone was willing to die for her husband.[8] Although he had a father and mother, the tenderness of her love so far exceeded theirs that she showed them to be strangers to their own son and only related to him in name; and so noble did this action of hers appear to the gods, as well as to men, that among the many who have done virtuously she is one of the very few to whom, in admiration of her noble action, they have granted the privilege of returning alive to earth. That shows how highly the gods too esteem loyalty and virtue in love. But Orpheus, the son of Oiagros, the harper, they sent away from the underworld empty-handed, and presented to him a phantom only of her whom he sought, but herself they would not give up,[9] because he showed no spirit; he was only a harp-player, and did not dare like Alkestis to die for love, but was contriving how he might enter Hades alive. Moreover, they afterwards caused him to suffer death at the hands of women as further punishment, and did not honour him as they did Achilles, the son of Thetis. Him they sent to the Islands of the Blest. His mother had warned him that if he killed Hektor he would be killed himself, but that if he didn't, he would return home and live to a good old age. Nevertheless, he gave his life to revenge his lover Patroklos, and dared to die, not only on his behalf, but after he was dead. The gods were full of admiration, and gave him outstanding honours, because he valued his lover so highly.” “Aischylos talks nonsense in claiming that it was Achilles who was in love with Patroklos,[10] for he was more beautiful than not only Patroklos but all the other heroes as well, and still beardless, and, as Homer says, far younger than him.[11] And greatly as the gods honour the virtue of love, the return of love on the part of the beloved to the lover is even more admired and valued and rewarded by them. That’s because the lover is more divine than the beloved, for he has the god within him. Wherefore the gods honoured him even above Alkestis, and sent him to the Islands of the Blest. “These are my reasons for affirming that Eros is the oldest and noblest and mightiest of the gods; and the chiefest author and giver of virtue and happiness, both in life and after death.” This, or something like this, was the speech of Phaidros; and some other speeches followed which Aristodemos did not remember; the next which he repeated was that of Pausanias[12]: “Phaidros, the argument has not been set before us, I think, quite in the right form;—we should not be called upon to praise Eros in such an indiscriminate manner. If there were only one Eros, then what you said would be well enough; but since there isn’t, we should have begun by determining which of them was to be the theme of our praises. I will amend this defect; and first of all I will tell you which Eros is deserving of praise, and then try to hymn the praiseworthy one in a manner worthy of him. “For we all know that Eros is inseparable from Aphrodite, and were she only one, there would be only one Eros; but as there are two goddesses there must be two Erotes. And am I not right in asserting that there are two goddesses? The elder one, having no mother, who is called the heavenly Aphrodite—she is the daughter of Heaven[13]; the younger, who is the daughter of Zeus and Dione—her we call common[14]; and the Eros who is her fellow-worker is rightly named common, as the other love is called heavenly. All the gods ought to have praise given to them, but not without distinction of their natures; and therefore I must try to distinguish the characters of each.  “Now actions vary according to the manner of their performance. Take, for example, that which we are now doing, drinking, singing and talking—these actions are not in themselves either good or evil, but they turn out in this or that way according to the mode of performing them; and when well done they are good, and when wrongly done they are evil; and in like manner not every Eros, but only that which has a noble purpose, is noble and worthy of praise. “The Eros who is the offspring of the common Aphrodite is essentially common, and has no discrimination, being such as the meaner sort of men feel. Those of this sort are, first, as likely to fall in love with women as with boys. Secondly, they are in love with their bodies rather than their souls. Thirdly, the most foolish beings are the objects of this love which desires only to gain an end, but never thinks of accomplishing the end nobly, and therefore does good and evil quite indiscriminately. The goddess who is his mother is far younger than the other, and she was born of the union of the male and female, and partakes of both. “But the other Eros springs from the heavenly Aphrodite, who, first of all, does not partake of female, but only of male (and this is the love of boys), and secondly, is the elder and has no part in outrage. Therefore, those who are inspired by this love turn to the male, attracted by what is more vigorous and has more sense. And one may recognise amongst those who love boys the ones whose love is of this kind; for they only love boys old enough to have sense, and that is much about the time at which their beards begin to grow. “For those who start loving a boy at this point in time are in a position I believe to be with him and live with him for their whole life and not—having taken them in their inexperience, and deceived them — to play the fool with them, or run away from one to another of them. But the love of young boys should be forbidden by law,[15] to stop so much energy being thrown away for an uncertain result, as it is not known how good or bad, in mind or body, young boys will eventually turn out. The good willingly observe this rule, but the coarser sort of lovers ought to be compelled to, just as we stop them, so far as we can, falling in love with women of free birth. These are the persons who bring a reproach on love; so that some people even go so far as to say that it is wrong to satisfy your lover. They say this having in mind the common lovers, observing their impropriety and injustice; for surely nothing that is decorously and lawfully done can justly be censured.  “Now here and in Sparta the rules about love are perplexing, but in most cities they are simple and easily intelligible; in Elis and Boiotia, and in countries having no gifts of eloquence, they are very straightforward; the law is simply in favour of these connexions, and no one, whether young or old, has anything to say to their discredit; the reason being, as I suppose, that they are men of few words in those parts, and therefore the lovers do not like the trouble of pleading their suit. In Ionia and other places, and generally in countries which are subject to the barbarians, the custom is held to be shameful. In the eyes of barbarians, on account of their tyrannies, pederasty as well as philosophy and the love of gymnastics is shameful; for it is not in the interests of rulers that their subjects should have noble thoughts, any more than strong friendships or attachments, which these activities, and love in particular, is likely to inspire, as our Athenian tyrants learned by experience; for the love of Aristogeiton and the constancy of Harmodios had a strength which undid their power.[16] “So wherever it has been laid down as shameful to satisfy lovers, it has been through the vice of those who have done so — the self-seeking of the governors and the cowardice of the governed; and the belief that the satisfying of lovers is always right is attributable to the mental laziness. “In our own country much finer customs prevail, but, as I was saying, the explanation of it is rather perplexing. For, observe that open loves are held to be more honourable than secret ones, and that the love of the noblest and highest, even if their persons are less beautiful than others, is especially honourable. Consider, too, how great is the encouragement which everyone gives to the lover. He is not regarded as doing anything shameful: if he succeeds he is praised, and if he fails he is blamed. And in the pursuit of his love the custom of mankind allows him to be praised for doing amazing things, things which if he did with any other aim, would reap the greatest reproaches. For if, in wanting money or office or any position, he behaved like this – making all sorts of supplications and beseechings in his requests, swearing oaths, sleeping outside the boy’s front door, and performing acts of slavery that no slave would put up with—he would be told to stop by friends and enemies alike, the former reproaching him for his flatteries and servilities, the latter admonishing him and feeling ashamed on his behalf. But the actions of a lover have a grace which ennobles them; and custom has decided that they are highly commendable and that there no loss of character in them; and, what is strangest of all, he only may swear and forswear himself (so men say), and the gods will forgive his transgression, for there is no such thing as a lover's oath.  “Such is the entire liberty which gods and men have allowed the lover, according to the custom which prevails in our part of the world. From this point of view a man fairly argues that in Athens both to love and to be friendly to lovers are held to be very honourable things. But when fathers give their sons escorts when men fall in love with them, and forbid them to talk to their lovers, and those are the escort's instructions as well, and the boy’s companions and equals blame him if they see anything of the sort, and their elders refuse to silence the reprovers and do not rebuke them—then, any one who reflects on all this will, on the contrary, think that we hold these practices to be most shameful. “But, as I was saying at first, the truth, I believe, is that whether such practices are honourable or whether they are dishonourable is not a simple question; they are honourable to him who follows them honourably, dishonourable to him who follows them dishonourably. It is base to satisfy one who is no good or for the wrong reasons, while it is noble to satisfy the good and for the right reasons. It is the common lover who is no good, the one in love with the body rather than the soul, inasmuch as he is not even a lasting lover, because he loves a thing which is not lasting either. As soon as the youthful bloom of the body fades—which is what he was in love with—'he takes wing and flies away,’ making a mockery of all his words and promises. Whereas he who loves a boy for his good character remains throughout life, for he has attached himself to what is lasting. “The custom of our country would have both of them tested well and truly, and would have us yield to the one sort of lover and avoid the other, and therefore encourages some to pursue, and others to fly; testing both the lover and beloved in contests and trials, until they show to which of the two classes they respectively belong. And this is the reason why, in the first place, a hasty attachment is held to be dishonourable, because time is the true test of this as of most other things; and secondly there is a dishonour in being overcome by the love of money or political power, whether a boy is frightened into yielding by the loss of them, or, having experienced the benefits of money and political corruption, is unable to turn them down, for neither of these things is likely to be stable or lasting nature, not to mention that no noble friendship ever sprang from them. “There remains, then, only one way our customs allow the boy to gratify his lover with honour. It is permissible, as I have said, for a lover to enter upon any kind of voluntary slavery he may choose to the boy he loves, and this is agreed not to be flattery or in any way demeaning. Likewise, there is one other kind of voluntary slavery which is not regarded as demeaning. This is the slavery of the boy, in his desire for improvement. It can happen that a boy chooses to serve another under the idea that he will be improved by him either in wisdom, or in some other particular of virtue. This willing enslavement is not to be regarded as a dishonour, and is not open to the charge of flattery. “And these two customs, one about pederasty, and the other about philosophy and virtue in general, ought to meet in one, and then the boy may honourably indulge his lover. For when the lover and the boy have the same aim, and each has the approval of convention—the lover because he is justified in performing any service he chooses for a boy who has granted his favours, the boy because he is justified in submitting, in any way he will, to the man who can make him wise and good. So if the lover is capable of communicating wisdom and virtue, and if the boy is seeking to acquire them with a view to education and wisdom, then, and only then, this favourable combination makes it noble for a boy to gratify his lover. In any other circumstances, it is not.  “Nor when love is of this disinterested sort is there any disgrace in being deceived, but in every other case there is equal disgrace in being or not being deceived. For he who is gracious to his lover under the impression that he is rich, and is disappointed of his gains because he turns out to be poor, is disgraced all the same: for a boy who does this is thought to be displaying his true character as one who would do anything for anyone for the sake of money, and this is not honourable. And on the same principle he who gives himself to a lover because he is a good man, and in the hope that he will be improved by his company, shows himself to be virtuous, even though the object of his affection turn out to be a villain, and to have no virtue; and if he is deceived he has committed a noble error. For he has proved that for his part he will do anything for anybody with a view to virtue and improvement, than which there can be nothing nobler. “Thus noble in every case is the granting of one’s favours for the sake of virtue. This is the love of the heavenly goddess, and is heavenly, and of great price to individuals and cities, making both lover and boy eager in furthering their own improvement. But all other loves are the offspring of the other goddess, the common one. “To you, Phaidros, I offer this my contribution in praise of Eros, which is as good as I could make extempore. |

Πρῶτον μὲν γάρ, ὥσπερ λέγω, ἔφη Φαῖδρον ἀρξάμενον ἐνθένδε ποθὲν λέγειν, ὅτι μέγας θεὸς εἴη ὁ Ἔρως καὶ θαυμαστὸς ἐν ἀνθρώποις τε καὶ θεοῖς, πολλαχῇ μὲν καὶ ἄλλῃ, οὐχ ἥκιστα δὲ [b] κατὰ τὴν γένεσιν. τὸ γὰρ ἐν τοῖς πρεσβύτατον εἶναι τὸν θεὸν τίμιον, ἦ δ᾿ ὅς· τεκμήριον δὲ τούτου· γονῆς γὰρ Ἔρωτος οὔτ᾿ εἰσὶν οὔτε λέγονται ὑπ᾿ οὐδενὸς οὔτε ἰδιώτου οὔτε ποιητοῦ, ἀλλ᾿ Ἡσίοδος πρῶτον μὲν χάος φησὶ γενέσθαι, αὐτὰρ ἔπειτα φησὶ μετὰ τὸ χάος δύο τούτω γενέσθαι, Γῆν τε καὶ Ἔρωτα. Παρμενίδης δὲ τὴν Γένεσιν λέγει πρώτιστον μὲν Ἔρωτα θεῶν μητίσατο πάντων. [c]  Ἡσιόδῳ δὲ καὶ Ἀκουσίλεως ὁμολογεῖ·[17] Οὕτω πολλαχόθεν ὁμολογεῖται ὁ Ἔρως ἐν τοῖς πρεσβύτατος εἶναι. πρεσβύτατος δὲ ὢν μεγίστων ἀγαθῶν ἡμῖν αἴτιός ἐστιν. οὐ γὰρ ἔγωγ᾿ ἔχω εἰπεῖν ὅ τι μεῖζόν ἐστιν ἀγαθὸν εὐθὺς νέῳ ὄντι ἢ ἐραστὴς χρηστὸς καὶ ἐραστῇ παιδικά. ὃ γὰρ χρὴ ἀνθρώποις ἡγεῖσθαι παντὸς τοῦ βίου τοῖς μέλλουσι καλῶς βιώσεσθαι, τοῦτο οὔτε συγγένεια οἵα τε ἐμποιεῖν οὕτω καλῶς οὔτε τιμαὶ οὔτε πλοῦτος [d]οὔτ᾿ ἄλλο οὐδὲν ὡς ἔρως. λέγω δὲ δὴ τί τοῦτο; τὴν ἐπὶ μὲν τοῖς αἰσχροῖς αἰσχύνην, ἐπὶ δὲ τοῖς καλοῖς φιλοτιμίαν· οὐ γὰρ ἔστιν ἄνευ τούτων οὔτε πόλιν οὔτε ἰδιώτην μεγάλα καὶ καλὰ ἔργα ἐξεργάζεσθαι. φημὶ τοίνυν ἐγὼ ἄνδρα ὅστις ἐρᾷ, εἴ τι αἰσχρὸν ποιῶν κατάδηλος γίγνοιτο ἢ πάσχων ὑπό του δι᾿ ἀνανδρίαν μὴ ἀμυνόμενος, οὔτ᾿ ἂν ὑπὸ πατρὸς ὀφθέντα οὕτως ἀλγῆσαι οὔτε ὑπὸ ἑταίρων οὔτε ὑπ᾿ ἄλλου οὐδενὸς ὡς ὑπὸ παιδικῶν. [e] ταὐτὸν δὲ τοῦτο καὶ τὸν ἐρώμενον ὁρῶμεν, ὅτι διαφερόντως τοὺς ἐραστὰς αἰσχύνεται, ὅταν ἀφθῇ ἐν αἰσχρῷ τινὶ ὥν. εἰ οὖν μηχανή τις γένοιτο ὥστε πόλιν γενέσθαι ἢ στρατόπεδον ἐραστῶν τε καὶ παιδικῶν, οὐκ ἔστιν ὅπως ἂν ἄμεινον οἰκήσειαν τὴν ἑαυτῶν ἢ ἀπεχόμενοι πάντων τῶν αἰσχρῶν [179a] καὶ φιλοτιμούμενοι πρὸς ἀλλήλους· καὶ μαχόμενοί γ᾿ ἂν μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων οἱ τοιοῦτοι νικῷεν ἂν ὀλίγοι ὄντες, ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν, πάντας ἀνθρώπους. ἐρῶν γὰρ ἀνὴρ ὑπὸ παιδικῶν ὀφθῆναι ἢ λιπὼν τάξιν ἢ ὅπλα ἀποβαλὼν ἧττον ἂν δήπου δέξαιτο ἢ ὑπὸ πάντων τῶν ἄλλων, καὶ πρὸ τούτου τεθνάναι ἂν πολλάκις ἕλοιτο· καὶ μὴν ἐγκαταλιπεῖν γε τὰ παιδικὰ ἢ μὴ βοηθῆσαι κινδυνεύοντι, οὐδεὶς οὕτω κακὸς ὅντινα οὐκ ἂν αὐτὸς ὁ Ἔρως ἔνθεον ποιήσειε πρὸς ἀρετήν, ὥσθ᾿ ὅμοιον εἶναι τῷ ἀρίστῳ [b] φύσει. καὶ ἀτεχνῶς, ὃ ἔφη Ὅμηρος, “μένος ἐμπνεῦσαι” ἐνίοις τῶν ἡρώων τὸν θεόν, τοῦτο ὁ Ἔρως τοῖς ἐρῶσι παρέχει γιγνόμενον παρ᾿ αὑτοῦ. Καὶ μὴν ὑπεραποθνῄσκειν γε μόνοι ἐθέλουσιν οἱ ἐρῶντες, οὐ μόνον ὅτι ἄνδρες, ἀλλὰ καὶ αἱ γυναῖκες. τούτου δὲ καὶ ἡ Πελίου θυγάτηρ Ἄλκηστις ἱκανὴν μαρτυρίαν παρέχεται ὑπὲρ τοῦδε τοῦ λόγου εἰς τοὺς Ἕλληνας, ἐθελήσασα μόνη ὑπὲρ τοῦ αὐτῆς ἀνδρὸς ἀποθανεῖν, ὄντων αὐτῷ [c] πατρός τε καὶ μητρός· οὓς ἐκείνη τοσοῦτον ὑπερεβάλετο τῇ φιλίᾳ διὰ τὸν ἔρωτα, ὥστε ἀποδεῖξαι αὐτοὺς ἀλλοτρίους ὄντας τῷ υἱεῖ καὶ ὀνόματι μόνον προσήκοντας· καὶ τοῦτ᾿ ἐργασαμένη τὸ ἔργον οὕτω καλὸν ἔδοξεν ἐργάσασθαι οὐ μόνον ἀνθρώποις ἀλλὰ καὶ θεοῖς, ὥστε πολλῶν πολλὰ καὶ καλὰ ἐργασαμένων εὐαριθμήτοις δή τισιν ἔδοσαν τοῦτο γέρας οἱ θεοί, ἐξ Ἅιδου ἀνεῖναι πάλιν τὴν ψυχήν, ἀλλὰ τὴν ἐκείνης ἀνεῖσαν ἀγασθέντες τῷ [d] ἔργῳ· οὕτω καὶ θεοὶ τὴν περὶ τὸν ἔρωτα σπουδήν τε καὶ ἀρετὴν μάλιστα τιμῶσιν. Ὀρφέα δὲ τὸν Οἰάγρου ἀτελῆ ἀπέπεμψαν ἐξ Ἅιδου, φάσμα δείξαντες τῆς γυναικὸς ἐφ᾿ ἣν ἧκεν, αὐτὴν δὲ οὐ δόντες, ὅτι μαλθακίζεσθαι ἐδόκει, ἅτε ὢν κιθαρῳδός, καὶ οὐ τολμᾶν ἕνεκα τοῦ ἔρωτος ἀποθνῄσκειν ὥσπερ Ἄλκηστις, ἀλλὰ διαμηχανᾶσθαι ζῶν εἰσιέναι εἰς Ἅιδου. τοιγάρτοι διὰ ταῦτα δίκην αὐτῷ ἐπέθεσαν, καὶ ἐποίησαν τὸν θάνατον αὐτοῦ [e] ὑπὸ γυναικῶν γενέσθαι, οὐχ ὥσπερ Ἀχιλλέα τὸν τῆς Θέτιδος υἱὸν ἐτίμησαν καὶ εἰς μακάρων νήσους ἀπέπεμψαν, ὅτι πεπυσμένος παρὰ τῆς μητρὸς ὡς ἀποθανοῖτο ἀποκτείνας Ἕκτορα, μὴ ἀποκτείνας δὲ τοῦτον οἴκαδ᾿ ἐλθὼν γηραιὸς τελευτήσοι, ἐτόλμησεν ἑλέσθαι βοηθήσας τῷ ἐραστῇ Πατρόκλῳ [180a] καὶ τιμωρήσας οὐ μόνον ὑπεραποθανεῖν ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐπαποθανεῖν τετελευτηκότι· ὅθεν δὴ καὶ ὑπεραγασθέντες οἱ θεοὶ διαφερόντως αὐτὸν ἐτίμησαν, ὅτι τὸν ἐραστὴν οὕτω περὶ πολλοῦ ἐποιεῖτο.  Αἰσχύλος δὲ φλυαρεῖ φάσκων Ἀχιλλέα Πατρόκλου ἐρᾶν, ὃς ἦν καλλίων οὐ μόνον Πατρόκλου ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν ἡρώων ἁπάντων, καὶ ἔτι ἀγένειος, ἔπειτα νεώτερος πολύ, ὥς φησιν Ὅμηρος. ἀλλὰ γὰρ τῷ [b] ὄντι μάλιστα μὲν ταύτην τὴν ἀρετὴν οἱ θεοὶ τιμῶσι τὴν περὶ τὸν ἔρωτα, μᾶλλον μέντοι θαυμάζουσι καὶ ἄγανται καὶ εὖ ποιοῦσιν, ὅταν ὁ ἐρώμενος τὸν ἐραστὴν ἀγαπᾷ, ἢ ὅταν ὁ ἐραστὴς τὰ παιδικά. θειότερον γὰρ ἐραστὴς παιδικῶν· ἔνθεος γάρ ἐστι. διὰ ταῦτα καὶ τὸν Ἀχιλλέα τῆς Ἀλκήστιδος μᾶλλον ἐτίμησαν, εἰς μακάρων νήσους ἀποπέμψαντες. Οὕτω δὴ ἔγωγέ φημι· Ἔρωτα θεῶν καὶ πρεσβύτατον καὶ τιμιώτατον καὶ κυριώτατον εἶναι εἰς ἀρετῆς καὶ εὐδαιμονίας κτῆσιν ἀνθρώποις καὶ ζῶσι καὶ τελευτήσασιν. [c] Φαῖδρον μὲν τοιοῦτόν τινα λόγον ἔφη εἰπεῖν, μετὰ δὲ Φαῖδρον ἄλλους τινὰς εἶναι, ὧν οὐ πάνυ διεμνημόνευεν· οὓς παρεὶς τὸν Παυσανίου λόγον διηγεῖτο. εἰπεῖν δ᾿ αὐτὸν ὅτι Οὐ καλῶς μοι δοκεῖ, ὦ Φαῖδρε, προβεβλῆσθαι ἡμῖν ὁ λόγος, τὸ ἁπλῶς οὕτως παρηγγέλθαι ἐγκωμιάζειν Ἔρωτα. εἰ μὲν γὰρ εἷς ἦν ὁ Ἔρως, καλῶς ἂν εἶχε· νῦν δὲ οὐ γάρ ἐστιν εἷς· μὴ ὄντος δὲ ἑνὸς ὀρθότερόν ἐστι [d] πρότερον προρρηθῆναι ὁποῖον δεῖ ἐπαινεῖν. ἐγὼ οὖν πειράσομαι τοῦτο ἐπανορθώσασθαι, πρῶτον μὲν Ἔρωτα φράσαι ὃν δεῖ ἐπαινεῖν, ἔπειτα ἐπαινέσαι ἀξίως τοῦ θεοῦ. πάντες γὰρ ἴσμεν ὅτι οὐκ ἔστιν ἄνευ Ἔρωτος Ἀφροδίτη. μιᾶς μὲν οὖν οὔσης εἷς ἂν ἦν Ἔρως· ἐπεὶ δὲ δὴ δύο ἐστόν, δύο ἀνάγκη καὶ Ἔρωτε εἶναι. πῶς δ᾿ οὐ δύο τὼ θεά; ἡ μέν γέ που πρεσβυτέρα καὶ ἀμήτωρ Οὐρανοῦ θυγάτηρ, ἣν δὴ καὶ Οὐρανίαν ἐπονομάζομεν· ἡ δὲ νεωτέρα Διὸς καὶ Διώνης, ἣν δὴ Πάνδημον καλοῦμεν. [e] ἀναγκαῖον δὴ καὶ Ἔρωτα τὸν μὲν τῇ ἑτέρᾳ συνεργὸν Πάνδημον ὀρθῶς καλεῖσθαι, τὸν δὲ Οὐράνιον. ἐπαινεῖν μὲν οὖν δεῖ πάντας θεούς, ἃ δ᾿ οὖν ἑκάτερος εἴληχε πειρατέον εἰπεῖν. πᾶσα [181] γὰρ πρᾶξις ὧδ᾿ ἔχει· αὐτὴ ἐφ᾿ ἑαυτῆς πραττομένη οὔτε καλὴ οὔτε αἰσχρά. οἷον ὃ νῦν ἡμεῖς ποιοῦμεν, ἢ πίνειν ἢ ᾄδειν ἢ διαλέγεσθαι, οὐκ ἔστι τούτων αὐτὸ καλὸν οὐδέν, ἀλλ᾿ ἐν τῇ πράξει, ὡς ἂν πραχθῇ, τοιοῦτον ἀπέβη· καλῶς μὲν γὰρ πραττόμενον καὶ ὀρθῶς καλὸν γίγνεται, μὴ ὀρθῶς δὲ αἰσχρόν. οὕτω δὴ καὶ τὸ ἐρᾶν καὶ ὁ Ἔρως οὐ πᾶς ἐστὶ καλὸς οὐδὲ ἄξιος ἐγκωμιάζεσθαι, ἀλλ᾿ ὁ καλῶς προτρέπων ἐρᾶν.  Ὁ μὲν οὖν τῆς Πανδήμου Ἀφροδίτης ὡς [b] ἀληθῶς πάνδημός ἐστι καὶ ἐξεργάζεται ὅ τι ἂν τύχῃ· καὶ οὗτός ἐστιν ὃν οἱ φαῦλοι τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἐρῶσιν. ἐρῶσι δὲ οἱ τοιοῦτοι πρῶτον μὲν οὐχ ἧττον γυναικῶν ἢ παίδων, ἔπειτα ὧν καὶ ἐρῶσι τῶν σωμάτων μᾶλλον ἢ τῶν ψυχῶν, ἔπειτα ὡς ἂν δύνωνται ἀνοητοτάτων, πρὸς τὸ διαπράξασθαι μόνον βλέποντες, ἀμελοῦντες δὲ τοῦ καλῶς ἢ μή. ὅθεν δὴ συμβαίνει αὐτοῖς, ὅ τι ἂν τύχωσι, τοῦτο πράττειν, ὁμοίως μὲν ἀγαθόν, ὁμοίως δὲ τοὐναντίον. [c] ἔστι γὰρ καὶ ἀπὸ τῆς θεοῦ νεωτέρας τε οὔσης πολὺ ἢ τῆς ἑτέρας, καὶ μετεχούσης ἐν τῇ γενέσει καὶ θήλεος καὶ ἄρρενος. ὁ δὲ τῆς Οὐρανίας πρῶτον μὲν οὐ μετεχούσης θήλεος ἀλλ᾿ ἄρρενος μόνον· [καὶ ἔστιν οὗτος ὁ τῶν παίδων ἔρως·] ἔπειτα πρεσβυτέρας, ὕβρεως ἀμοίρου· ὅθεν δὴ ἐπὶ τὸ ἄρρεν τρέπονται οἱ ἐκ τούτου τοῦ ἔρωτος ἔπιπνοι, τὸ φύσει ἐρρωμενέστερον καὶ νοῦν μᾶλλον ἔχον ἀγαπῶντες. καί τις ἂν γνοίη καὶ ἐν αὐτῇ τῇ παιδεραστίᾳ τοὺς εἱλικρινῶς ὑπὸ τούτου τοῦ ἔρωτος [d] ὡρμημένους· οὐ γὰρ ἐρῶσι παίδων, ἀλλ᾿ ἐπειδὰν ἤδη ἄρχωνται νοῦν ἴσχειν· τοῦτο δὲ πλησιάζει τῷ γενειάσκειν. παρεσκευασμένοι γάρ, οἶμαι, εἰσὶν οἱ ἐντεῦθεν ἀρχόμενοι ἐρᾶν ὡς τὸν βίον ἅπαντα συνεσόμενοι καὶ κοινῇ συμβιωσόμενοι, ἀλλ᾿ οὐκ ἐξαπατήσαντες, ἐν ἀφροσύνῃ λαβόντες ὡς νέον, καταγελάσαντες οἰχήσεσθαι ἐπ᾿ ἄλλον ἀποτρέχοντες. χρῆν δὲ καὶ νόμον εἶναι μὴ ἐρᾶν [e] παίδων, ἵνα μὴ εἰς ἄδηλον νολλὴ σπουδὴ ἀνηλίσκετο· τὸ γὰρ τῶν παίδων τέλος ἄδηλον οἷ τελευτᾷ κακίας καὶ ἀρετῆς ψυχῆς τε πέρι καὶ σώματος. οἱ μὲν οὖν ἀγαθοὶ τὸν νόμον τοῦτον αὐτοὶ αὑτοῖς ἑκόντες τίθενται, χρῆν δὲ καὶ τούτους τοὺς πανδήμους ἐραστὰς προσαναγκάζειν τὸ τοιοῦτον, [182a] ὥσπερ καὶ τῶν ἐλευθέρων γυναικῶν προσαναγκάζομεν αὐτοὺς καθ᾿ ὅσον δυνάμεθα μὴ ἐρᾶν. οὗτοι γάρ εἰσιν οἱ καὶ τὸ ὄνειδος πεποιηκότες, ὥστε τινας τολμᾶν λέγειν ὡς αἰσχρὸν χαρίζεσθαι ἐρασταῖς· λέγουσι δὲ εἰς τούτους ἀποβλέποντες, ὁρῶντες αὐτῶν τὴν ἀκαιρίαν καὶ ἀδικίαν, ἐπεὶ οὐ δήπου κοσμίως γε καὶ νομίμως ὁτιοῦν πραττόμενον ψόγον ἂν δικαίως φέροι. Καὶ δὴ καὶ ὁ περὶ τὸν ἔρωτα νόμος ἐν μὲν ταῖς ἄλλαις πόλεσι νοῆσαι ῥᾴδιος· ἁπλῶς γὰρ ὥρισται· ὁ δ᾿ ἐνθάδε [καὶ ἐν Λακεδαίμονι] ποικίλος. ἐν [b] Ἤλιδι μὲν γὰρ καὶ ἐν Βοιωτοῖς, καὶ οὗ μὴ σοφοὶ λέγειν, ἁπλῶς νενομοθέτηται καλὸν τὸ χαρίζεσθαι ἐρασταῖς, καὶ οὐκ ἄν τις εἴποι οὔτε νέος οὔτε παλαιὸς ὡς αἰσχρόν, ἵνα, οἶμαι, μὴ πράγματ᾿ ἔχωσι λόγῳ πειρώμενοι πείθειν τοὺς νέους, ἅτε ἀδύνατοι λέγειν· τῆς δὲ Ἰωνίας καὶ ἄλλοθι πολλαχοῦ αἰσχρὸν νενόμισται, ὅσοι ὑπὸ βαρβάροις οἰκοῦσι. τοῖς [c] γὰρ βαρβάροις διὰ τὰς τυραννίδας αἰσχρὸν τοῦτό τε καὶ ἥ γε φιλοσοφία καὶ ἡ φιλογυμναστία· οὐ γάρ, οἶμαι, συμφέρει τοῖς ἄρχουσι φρονήματα μεγάλα ἐγγίγνεσθαι τῶν ἀρχομένων, οὐδὲ φιλίας ἰσχυρὰς καὶ κοινωνίας, ὃ δὴ μάλιστα φιλεῖ τά τε ἄλλα πάντα καὶ ὁ ἔρως ἐμποιεῖν. ἔργῳ δὲ τοῦτο ἔμαθον καὶ οἱ ἐνθάδε τύραννοι· ὁ γὰρ Ἀριστογείτονος ἔρως καὶ ἡ Ἁρμοδίου φιλία βέβαιος γενομένη κατέλυσεν αὐτῶν τὴν ἀρχή.  οὕτως οὗ μὲν αἰσχρὸν ἐτέθη χαρίζεσθαι ἐρασταῖς, κακίᾳ τῶν [d] θεμένων κεῖται, τῶν μὲν ἀρχόντων πλεονεξίᾳ, τῶν δὲ ἀρχομένων ἀνανδρίᾳ· οὗ δὲ καλὸν ἁπλῶς ἐνομίσθη, διὰ τὴν τῶν θεμένων τῆς ψυχῆς ἀργίαν. ἐνθάδε δὲ πολὺ τούτων κάλλιον νενομοθέτηται, καὶ ὅπερ εἶπον, οὐ ῥᾴδιον κατανοῆσαι. Ἐνθυμηθέντι γὰρ ὅτι λέγεται κάλλιον τὸ φανερῶς ἐρᾶν τοῦ λάθρᾳ, καὶ μάλιστα τῶν γενναιοτάτων καὶ ἀρίστων, κἂν αἰσχίους ἄλλων ὦσι, καὶ ὅτι αὖ ἡ παρακέλευσις τῷ ἐρῶντι παρὰ πάντων [e] θαυμαστή. οὐχ ὥς τι αἰσχρὸν ποιοῦντι, καὶ ἑλόντι τε καλὸν δοκεῖ εἶναι καὶ μὴ ἑλόντι αἰσχρόν, καὶ πρὸς τὸ ἐπιχειρεῖν ἑλεῖν ἐξουσίαν ὁ νόμος δέδωκε τῷ ἐραστῇ θαυμαστὰ ἔργα ἐργαζομένῳ ἐπαινεῖσθαι, ἃ εἴ τις τολμῴη ποιεῖν ἄλλ᾿ ὁτιοῦν [183a] διώκων καὶ βουλόμενος διαπράξασθαι πλὴν τοῦτο [φιλοσοφίας], τὰ μέγιστα καρποῖτ᾿ ἂν ὀνείδη· εἰ γὰρ ἢ χρήματα βουλόμενος παρά του λαβεῖν ἢ ἀρχὴν ἄρξαι ἤ τιν᾿ ἄλλην δύναμιν ἐθέλοι ποιεῖν οἷάπερ οἱ ἐρασταὶ πρὸς τὰ παιδικά, ἱκετείας τε καὶ ἀντιβολήσεις ἐν ταῖς δεήσεσι ποιούμενοι, καὶ ὅρκους ὀμνύντες, καὶ κοιμήσεις ἐπὶ θύραις, καὶ ἐθέλοντες δουλείας δουλεύειν οἵας οὐδ᾿ ἂν δοῦλος οὐδείς, ἐμποδίζοιτο ἂν μὴ πράττειν οὕτω τὴν [b] πρᾶξιν καὶ ὑπὸ φίλων καὶ ὑπὸ ἐχθρῶν, τῶν μὲν ὀνειδιζόντων κολακείας καὶ ἀνελευθερίας, τῶν δὲ νουθετούντων καὶ αἰσχυνομένων ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν· τῷ δ᾿ ἐρῶντι πάντα ταῦτα ποιοῦντι χάρις ἔπεστι, καὶ δέδοται ὑπὸ τοῦ νόμου ἄνευ ὀνείδους πράττειν, ὡς πάγκαλόν τι πρᾶγμα διαπραττομένου· ὃ δὲ δεινότατον, ὥς γε λέγουσιν οἱ πολλοί, ὅτι καὶ ὀμνύντι μόνῳ συγγνώμη παρὰ θεῶν ἐκβάντι τὸν ὅρκον· ἀφροδίσιον γὰρ ὅρκον οὔ φασιν εἶναι· οὕτω καὶ οἱ [c] θεοὶ καὶ οἱ ἄνθρωποι πᾶσαν ἐξουσίαν πεποιήκασι τῷ ἐρῶντι, ὡς ὁ νόμος φησὶν ὁ ἐνθάδε. ταύτῃ μὲν οὖν οἰηθείη ἄν τις πάγκαλον νομίζεσθαι ἐν τῇδε τῇ πόλει καὶ τὸ ἐρᾶν καὶ τὸ φίλους γίγνεσθαι τοῖς ἐρασταῖς. ἐπειδὰν δὲ παιδαγωγοὺς ἐπιστήσαντες οἱ πατέρες τοῖς ἐρωμένοις μὴ ἐῶσι διαλέγεσθαι τοῖς ἐρασταῖς, καὶ τῷ παιδαγωγῷ ταῦτα προστεταγμένα ᾖ, ἡλικιῶται δὲ καὶ ἑταῖροι ὀνειδίζωσιν, [d] ἐάν τι ὁρῶσι τοιοῦτο γιγνόμενον, καὶ τοὺς ὀνειδίζοντας αὖ οἱ πρεσβύτεροι μὴ διακωλύωσι μηδὲ λοιδορῶσιν ὡς οὐκ ὀρθῶς λέγοντας, εἰς δὲ ταῦτά τις αὖ βλέψας ἡγήσαιτ᾿ ἂν πάλιν αἴσχιστον τὸ τοιοῦτον ἐνθάδε νομίζεσθαι. τὸ δέ, οἶμαι, ὧδ᾿ ἔχει· οὐχ ἁπλοῦν ἐστίν, ὅπερ ἐξ ἀρχῆς ἐλέχθη, οὔτε καλὸν εἶναι αὐτὸ καθ᾿ αὑτὸ οὔτε αἰσχρόν, ἀλλὰ καλῶς μὲν πραττόμενον καλόν, αἰσχρῶς δὲ αἰσχρόν. αἰσχρῶς μὲν οὖν ἐστὶ πονηρῷ τε καὶ πονηρῶς χαρίζεσθαι, καλῶς δὲ χρηστῷ τε καὶ καλῶς. πονηρὸς δ᾿ ἐστὶν ἐκεῖνος ὁ ἐραστὴς ὁ πάνδημος, ὁ τοῦ σώματος μᾶλλον ἢ τῆς ψυχῆς [e] ἐρῶν· καὶ γὰρ οὐδὲ μόνιμός ἐστιν, ἅτε οὐ μονίμου ἐρῶν πράγματος. ἅμα γὰρ τῷ τοῦ σώματος ἄνθει λήγοντι, οὗπερ ἤρα, “οἴχεται ἀποπτάμενος,” πολλοὺς λόγους καὶ ὑποσχέσεις καταισχύνας· ὁ δὲ τοῦ ἤθους χρηστοῦ ὄντος ἐραστὴς [184a] διὰ βίου μένει, ἅτε μονίμῳ συντακείς.  τούτους δὴ βούλεται ὁ ἡμέτερος νόμος εὖ καὶ καλῶς βασανίζειν, καὶ τοῖς μὲν χαρίσασθαι, τοὺς δὲ διαφεύγειν. διὰ ταῦτα οὖν τοῖς μὲν διώκειν παρακελεύεται, τοῖς δὲ φεύγειν, ἀγωνοθετῶν καὶ βασανίζων ποτέρων ποτέ ἐστιν ὁ ἐρῶν καὶ ποτέρων ὁ ἐρώμενος. οὕτω δὴ ὑπὸ ταύτης τῆς αἰτίας πρῶτον μὲν τὸ ἁλίσκεσθαι ταχὺ αἰσχρὸν νενόμισται, ἵνα χρόνος ἐγγένηται, ὃς δὴ δοκεῖ τὰ πολλὰ καλῶς βασανίζειν· ἔπειτα τὸ ὑπὸ χρημάτων καὶ ὑπὸ πολιτικῶν [b] δυνάμεων ἁλῶναι αἰσχρόν, ἐάν τε κακῶς πάσχων πτήξῃ καὶ μὴ καρτερήσῃ, ἄν τ᾿ εὐεργετούμενος εἰς χρήματα ἢ εἰς διαπράξεις πολιτικὰς μὴ καταφρονήσῃ· οὐδὲν γὰρ δοκεῖ τούτων οὔτε βέβαιον οὔτε μόνιμον εἶναι, χωρὶς τοῦ μηδὲ πεφυκέναι ἀπ᾿ αὐτῶν γενναίαν φιλίαν· μία δὴ λείπεται τῷ ἡμετέρῳ νόμῳ ὁδός, εἰ μέλλει καλῶς χαριεῖσθαι [c] ἐραστῇ παιδικά. ἔστι γὰρ ἡμῖν νόμος, ὥσπερ ἐπὶ τοῖς ἐρασταῖς ἦν δουλεύειν ἐθέλοντα ἡντινοῦν δουλείαν παιδικοῖς μὴ κολακείαν εἶναι μηδὲ ἐπονείδιστον, οὕτω δὴ καὶ ἄλλη μία μόνη δουλεία ἑκούσιος λείπεται οὐκ ἐπονείδιστος· αὕτη δέ ἐστιν ἡ περὶ τὴν ἀρετήν. Νενόμισται γὰρ δὴ ἡμῖν, ἐάν τις ἐθέλῃ τινὰ θεραπεύειν ἡγούμενος δι᾿ ἐκεῖνον ἀμείνων ἔσεσθαι ἢ κατὰ σοφίαν τινὰ ἢ κατὰ ἄλλο ὁτιοῦν μέρος ἀρετῆς, αὕτη αὖ ἡ ἐθελοδουλεία οὐκ αἰσχρὰ εἶναι οὐδὲ κολακεία. δεῖ δὴ τὼ νόμω τούτω συμβαλεῖν [d] εἰς ταὐτόν, τόν τε περὶ τὴν παιδεραστίαν καὶ τὸν περὶ τὴν φιλοσοφίαν τε καὶ τὴν ἄλλην ἀρετήν, εἰ μέλλει συμβῆναι καλὸν γενέσθαι τὸ ἐραστῇ παιδικὰ χαρίσασθαι. ὅταν γὰρ εἰς τὸ αὐτὸ ἔλθωσιν ἐραστής τε καὶ παιδικά, νόμον ἔχων ἑκάτερος, ὁ μὲν χαρισαμένοις παιδικοῖς ὑπηρετῶν ὁτιοῦν δικαίως ἂν ὑπηρετεῖν, ὁ δὲ τῷ ποιοῦντι αὐτὸν σοφόν τε καὶ ἀγαθὸν δικαίως αὖ ὁτιοῦν ἂν ὑπουργῶν ὑπουργεῖν, καὶ ὁ μὲν δυνάμενος εἰς φρόνησιν [e] καὶ τὴν ἄλλην ἀρετὴν συμβάλλεσθαι, ὁ δὲ δεόμενος εἰς παίδευσιν καὶ τὴν ἄλλην σοφίαν κτᾶσθαι, τότε δὴ τούτων συνιόντων εἰς ταὐτὸν τῶν νόμων μοναχοῦ ἐνταῦθα συμπίπτει τὸ καλὸν εἶναι παιδικὰ ἐραστῇ χαρίσασθαι, ἄλλοθι δὲ οὐδαμοῦ. ἐπὶ τούτῳ καὶ ἐξαπατηθῆναι οὐδὲν αἰσχρόν· ἐπὶ δὲ τοῖς ἄλλοις πᾶσι καὶ ἐξαπατωμένῳ αἰσχύνην [185a] φέρει καὶ μή. εἰ γάρ τις ἐραστῇ ὡς πλουσίῳ πλούτου ἕνεκα χαρισάμενος ἐξαπατηθείη καὶ μὴ λάβοι χρήματα, ἀναφανέντος τοῦ ἐραστοῦ πένητος, οὐδὲν ἧττον αἰσχρόν· δοκεῖ γὰρ ὁ τοιοῦτος τό γε αὑτοῦ ἐπιδεῖξαι, ὅτι ἕνεκα χρημάτων ὁτιοῦν ἂν ὁτῳοῦν ὑπηρετοῖ, τοῦτο δὲ οὐ καλόν. κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν δὴ λόγον κἂν εἴ τις ὡς ἀγαθῷ χαρισάμενος καὶ αὐτὸς ὡς ἀμείνων ἐσόμενος διὰ τὴν φιλίαν τοῦ [b] ἐραστοῦ ἐξαπατηθείη, ἀναφανέντος ἐκείνου κακοῦ καὶ οὐ κεκτημένου ἀρετήν, ὅμως καλὴ ἡ ἀπάτη· δοκεῖ γὰρ αὖ καὶ οὗτος τὸ καθ᾿ αὑτὸν δεδηλωκέναι, ὅτι ἀρετῆς γ᾿ ἕνεκα καὶ τοῦ βελτίων γενέσθαι πᾶν ἂν παντὶ προθυμηθείη, τοῦτο δὲ αὖ πάντων κάλλιστον· οὕτω πάντως γε καλὸν ἀρετῆς ἕνεκα χαριζεσθαι. Οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ τῆς οὐρανίας θεοῦ ἔρως καὶ οὐράνιος καὶ πολλοῦ ἄξιος καὶ πόλει καὶ ἰδιώταις, πολλὴν ἐπιμέλειαν ἀναγκάζων ποιεῖσθαι πρὸς ἀρετὴν [c] τόν τε ἐρῶντα αὐτὸν αὑτοῦ καὶ τὸν ἐρώμενον· οἱ δ᾿ ἕτεροι πάντες τῆς ἑτέρας, τῆς πανδήμου. ταῦτά σοι, ἔφη, ὡς ἐκ τοῦ παραχρῆμα, ὦ Φαῖδρε, περὶ Ἔρωτος συμβάλλομαι. |

Next, Eryximachos delivers a speech (185e-188e) asserting from his medical knowledge that the two kinds of Eros described by Pausanias are respectively sources of harmony or disharmony within the human body. Then the pre-eminent comic playwright Aristophanes took his turn, which had been postponed due to hiccups, and began:[18]

189c-193d

|

"Well, Eryximachus, I do intend to speak in a rather different vein from that in which you and Pausanias spoke. Mankind, in my opinion, is quite unaware of the power of Eros. If they were aware of it, they would build great temples and altars to him and would be making him the greatest sacrifices, but, as it is, this is not done, though it most certainly ought to be. Of all the gods, Eros is the most friendly towards men. He is our helper, and cures those evils whose cure brings the greatest happiness to the human race. I'll try to explain his power to you, so you can spread the word to others. “In the first place, let me treat of the nature of man and what has happened to it; for the original human nature was not like the present, but different. The sexes were not two as they are now, but originally three in number; there was man, woman, and the union of the two. The name of the third has survived, though the phenomenon itself has vanished. One race combining both male and female was, in form and name alike, Androgynous, but now the name only survives as a term of reproach. “In the second place, the primeval man was round, his back and sides forming a circle; and he had four hands and four feet, one head with two faces, looking opposite ways, set on a round neck and precisely alike; also four ears, two sets of genitals, and the remainder to correspond. He could walk upright as men now do, backwards or forwards as he pleased, and he could also roll over and over at a great pace, turning on his four hands and four feet, eight in all, like tumblers going over and over with their legs in the air; this was when he wanted to run fast. |

Καὶ μήν, ὦ Ἐρυξίμαχε, εἰπεῖν τὸν Ἀριστοφάνη, ἄλλῃ γέ πῃ ἐν νῷ ἔχω λέγειν, ἢ ᾗ σύ τε καὶ Παυσανίας εἰπέτην. ἐμοὶ γὰρ δοκοῦσιν οἱ ἄνθρωποι παντάπασι τὴν τοῦ ἔρωτος δύναμιν οὐκ ᾐσθῆσθαι, ἐπεὶ αἰσθανόμενοί γε μέγιστ᾿ ἂν αὐτοῦ ἱερὰ κατασκευάσαι καὶ βωμούς, καὶ θυσίας ἂν ποιεῖν μεγίστας, οὐχ ὥσπερ νῦν τούτων οὐδὲν γίγνεται περὶ αὐτόν, δέον πάντων μάλιστα γίγνεσθαι. [d] ἔστι γὰρ θεῶν φιλανθρωπότατος, ἐπίκουρός τε ὢν τῶν ἀνθρώπων καὶ ἰατρὸς τούτων, ὧν ἰαθέντων μεγίστη εὐδαιμονία ἂν τῷ ἀνθρωπείῳ γένει εἴη. ἐγὼ οὖν πειράσομαι ὑμῖν εἰσηγήσασθαι τὴν δύναμιν αὐτοῦ, ὑμεῖς δὲ τῶν ἄλλων διδάσκαλοι ἔσεσθε. δεῖ δὲ πρῶτον ὑμᾶς μαθεῖν τὴν ἀνθρωπίνην φύσιν καὶ τὰ παθήματα αὐτῆς. ἡ γὰρ πάλαι ἡμῶν φύσις οὐχ αὕτη ἦν, ἥπερ νῦν, ἀλλ᾿ ἀλλοία. πρῶτον μὲν γὰρ τρία ἦν τὰ γένη τὰ τῶν ἀνθρώπων, [e] οὐχ ὥσπερ νῦν δύο, ἄρρεν καὶ θῆλυ, ἀλλὰ καὶ τρίτον προσῆν κοινὸν ὂν ἀμφοτέρων τούτων, οὗ νῦν ὄνομα λοιπόν, αὐτὸ δὲ ἠφάνισται· ἀνδρόγυνον γὰρ ἓν τότε μὲν ἦν καὶ εἶδος καὶ ὄνομα ἐξ ἀμφοτέρων κοινὸν τοῦ τε ἄρρενος καὶ θήλεος, νῦν δ᾿ οὐκ ἔστιν ἀλλ᾿ ἢ ἐν ὀνείδει ὄνομα κείμενον. ἔπειτα ὅλον ἦν ἑκάστου τοῦ ἀνθρώπου τὸ εἶδος στρογγύλον, νῶτον καὶ πλευρὰς κύκλῳ ἔχον, χεῖρας δὲ τέτταρας εἶχε, καὶ σκέλη τὰ ἴσα ταῖς χερσί, καὶ πρόσωπα δύ᾿ ἐπ᾿ [190a] αὐχένι κυκλοτερεῖ, ὅμοια πάντῃ· κεφαλὴν δ᾿ ἐπ᾿ ἀμφοτέροις τοῖς προσώποις ἐναντίοις κειμένοις μίαν, καὶ ὦτα τέτταρα, καὶ αἰδοῖα δύο, καὶ τἆλλα πάντα ὡς ἀπὸ τούτων ἄν τις εἰκάσειεν. ἐπορεύετο δὲ καὶ ὀρθὸν ὥσπερ νῦν, ὁποτέρωσε βουληθείη· καὶ ὁπότε ταχὺ ὁρμήσειε θεῖν, ὥσπερ οἱ κυβιστῶντες καὶ εἰς ὀρθὸν τὰ σκέλη περιφερόμενοι κυβι· στῶσι κύκλῳ, ὀκτὼ τότε οὖσι τοῖς μέλεσιν ἀπερειδόμενοι [b] ταχὺ ἐφέροντο κύκλῳ. |

|

“Now the sexes were three, and such as I have described them; because the sun, moon, and earth are three; and the man was originally the child of the sun, the woman of the earth, and the man-woman of the moon, which is made up of sun and earth, and they were all round and moved round and round like their parents. Terrible was their might and strength, and the thoughts of their hearts were great, and they made an attack upon the gods; of them is told the tale of Otys and Ephialtes who, as Homer says, dared to scale heaven, and would have laid hands upon the gods. Zeus and the other gods wondered what to do about them and couldn't decide. Should they kill them and annihilate the race with thunderbolts, as they had done the giants, then there would be an end of the sacrifices and worship which men offered to them; but, on the other hand, the gods could not suffer their insolence to be unrestrained. “At last, after a good deal of reflection, Zeus discovered a way. He said: 'Methinks I have a plan which will humble their pride and improve their manners; men shall continue to exist, but I will cut them in two and then they will be diminished in strength and increased in numbers; this will have the advantage of making them more profitable to us. They shall walk upright on two legs, and if they continue insolent and will not be quiet, I will split them again and they shall hop about on a single leg.' “He spoke and cut human beings in two, like a sorb-apple which is halved for pickling, or as you might divide an egg with a hair; and as he cut them one after another, he bade Apollo turn the face and half the neck around to face the cut (so that in seeing his own cutting the human being might be better behaved), and to heal the rest of their wounds. So he gave a turn to the face and by drawing together the skin from the sides all over that which in our language is called the belly (just like drawstring bags) he made one opening at the centre, which he fastened in a knot (the same which is called the navel); he also moulded the chest and took out most of the wrinkles, much as a shoemaker might smooth leather upon a last; he left a few, however, in the region of the belly and navel, as a reminder of what happened in those far-off days. |

ἦν δὲ διὰ ταῦτα τρία τὰ γένη καὶ τοιαῦτα, ὅτι τὸ μὲν ἄρρεν ἦν τοῦ ἡλίου τὴν ἀρχὴν ἔκγονον, τὸ δὲ θῆλυ τῆς γῆς, τὸ δὲ ἀμφοτέρων μετέχον τῆς σελήνης, ὅτι καὶ ἡ σελήνη ἀμφοτέρων μετέχει· περιφερῆ δὲ δὴ ἦν καὶ αὐτὰ καὶ ἡ πορεία αὐτῶν διὰ τὸ τοῖς γονεῦσιν ὅμοια εἶναι. ἦν οὖν τὴν ἰσχὺν δεινὰ καὶ τὴν ῥώμην, καὶ τὰ φρονήματα μεγάλα εἶχον, ἐπεχείρησαν δὲ τοῖς θεοῖς, καὶ ὃ λέγει Ὅμηρος περὶ [c] Ἐφιάλτου τε καὶ Ὤτου, περὶ ἐκείνων λέγεται, τὸ εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν ἀνάβασιν ἐπιχειρεῖν ποιεῖν, ὡς ἐπιθησομένων τοῖς θεοῖς. Ὁ οὖν Ζεὺς καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι θεοὶ ἐβουλεύοντο, ὅ τι χρὴ αὐτοὺς ποιῆσαι, καὶ ἠπόρουν· οὔτε γὰρ ὅπως ἀποκτείναιεν εἶχον καὶ ὥσπερ τοὺς γίγαντας κεραυνώσαντες τὸ γένος ἀφανίσαιεν—αἱ τιμαὶ γὰρ αὐτοῖς καὶ ἱερὰ τὰ παρὰ τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἠφανίζετο —οὔθ᾿ ὅπως ἐῷεν ἀσελγαίνειν. μόγις δὴ ὁ Ζεὺς ἐννοήσας λέγει ὅτι Δοκῶ μοι, ἔφη, ἔχειν μηχανήν, ὡς ἂν εἶέν τε ἄνθρωποι καὶ παύσαιντο τῆς ἀκολασίας [d] ἀσθενέστεροι γενόμενοι. νῦν μὲν γὰρ αὐτούς, ἔφη, διατεμῶ δίχα ἕκαστον, καὶ ἅμα μὲν ἀσθενέστεροι ἔσονται, ἅμα δὲ χρησιμώτεροι ἡμῖν διὰ τὸ πλείους τὸν ἀριθμὸν γεγονέναι· καὶ βαδιοῦνται ὀρθοὶ ἐπὶ δυοῖν σκελοῖν· ἐὰν δ᾿ ἔτι δοκῶσιν ἀσελγαίνειν καὶ μὴ ἐθέλωσιν ἡσυχίαν ἄγειν, πάλιν αὖ, ἔφη, τεμῶ δίχα, ὥστ᾿ ἐφ᾿ ἑνὸς πορεύσονται σκέλους ἀσκωλίζοντες· ταῦτα εἰπὼν ἔτεμεν τοὺς ἀνθρώπους δίχα, ὥσπερ οἱ τὰ ὄα τέμνοντες καὶ μέλλοντες ταριχεύειν, ἢ ὥσπερ οἱ τὰ ὠὰ ταῖς θριξίν· [e] ὅντινα δὲ τέμοι, τὸν Ἀπόλλω ἐκέλευε τό τε πρόσωπον μεταστρέφειν καὶ τὸ τοῦ αὐχένος ἥμισυ πρὸς τὴν τομήν, ἵνα θεώμενος τὴν αὑτοῦ τμῆσιν κοσμιώτερος εἴη ὁ ἄνθρωπος, καὶ τἆλλα ἰᾶσθαι ἐκέλευεν. ὁ δὲ τό τε πρόσωπον μετέστρεφε, καὶ συνέλκων πανταχόθεν τὸ δέρμα ἐπὶ τὴν γαστέρα νῦν καλουμένην, ὥσπερ τὰ σύσπαστα βαλλάντια, ἓν στόμα ποιῶν ἀπέδει κατὰ μέσην τὴν γαστέρα, [191a] ὃ δὴ τὸν ὀμφαλὸν καλοῦσι. καὶ τὰς μὲν ἄλλας ῥυτίδας τὰς πολλὰς ἐξελέαινε καὶ τὰ στήθη διήρθρου, ἔχων τι τοιοῦτον ὄργανον οἷον οἱ σκυτοτόμοι περὶ τὸν καλόποδα λεαίνοντες τὰς τῶν σκυτῶν ῥυτίδας· ὀλίγας δὲ κατέλιπε, τὰς περὶ αὐτὴν τὴν γαστέρα καὶ τὸν ὀμφαλόν, μνημεῖον εἶναι τοῦ παλαιοῦ πάθους. |

“After the division the two parts of man, each desiring his other half, came together, and throwing their arms about one another, entwined in mutual embraces, longing to grow into one, they were on the point of dying from hunger and self-neglect, because they did not like to do anything apart; and when one of the halves died and the other survived, the survivor sought another, either meeting half of a complete woman (and that is what we now call a woman), or half a complete man,—and clung to that. In this way they kept on dying. “Zeus in pity of them invented a new plan: he moved their genitals round to the front—for up till then they had them on the outside, and had reproduced not by copulation but by discharge on to the ground, like grasshoppers. So he moved their genitals to the front and thus made them use them for reproduction by insemination, the male in the female, so that if, in embracing, a man chanced upon a woman, they could produce children; or if male chanced upon male, they might get satisfaction from one another's company, then rest, and go their ways to the business of life. “So, ancient is the desire of one another which is implanted in us, reuniting our original nature, making one of two, and healing the state of man. Each of us is a mere fragment[19] of a human being, because we are sliced in two like fillets of sole and so each is always looking for his other half. Men who are a section of that double nature which was once called Androgynous are lovers of women; adulterers are generally of this breed. Similarly, women of this type are nymphomaniacs and adulteresses. The women who are a section of the woman do not care for men, but have female attachments; lesbians are of this sort. But they who are a section of the male follow the male, and while they are boys, being slices of the original male, they are fond of men and enjoy going to bed with men and embracing them. These are the best of boys and youths, because they have the most manly nature. Some indeed assert that they are shameless, but this is not true; for they do not act thus from any want of shame, but out of courage, manliness and masculinity, and they embrace that which is like themselves. And these when they grow up become our statesmen, and these only, which is a great proof of the truth of what I am saving. When they reach manhood they are lovers of boys, and are not naturally inclined to marry or beget children,—if at all, they do so only in obedience to custom; but they are satisfied if they may be allowed to live with one another unwedded. “One of this nature is inclined to love boys or (as a boy) inclined to have a lover, always embracing that which is akin to him. And when a lover of boys or a lover of another sort meets with his other half, the actual half of himself, whether he be a lover of youth or a lover of another sort, the pair are lost in an amazement of love and friendship and intimacy, and can hardly be induced to be out of one another's sight even for a moment. These are the people who pass their whole lives together; yet they can not explain what they desire of one another. No one imagines the intense yearning which each of them has towards the other is simply the desire for sexual intercourse, or that sex is the reason why one gets such enormous pleasure out of the other's company. The soul of each evidently desires something else which it cannot express, and of which it has only a dark and doubtful presentiment.  “Suppose Hephaistos, with his instruments, to come to the pair who are lying side by side and to say to them, 'What do you mortals want of one another?' they would be unable to explain. And suppose further, that when he saw their perplexity he said: 'Do you desire to be wholly one; always day and night to be in one another's company? for if this is what you desire, I am ready to melt you into one and let you grow together, so that being two you shall become one, and while you live live a common life as if you were a single man, and, after your death, down in Hades, still be one departed soul instead of two—I ask whether this is what you lovingly desire, and whether you are satisfied to attain this?'—there is not a man of them who when he heard the proposal would deny or would not acknowledge that this meeting and melting into one another, this becoming one instead of two, was the very expression of his ancient need. “And the reason is that human nature was originally one and we were a whole, and the desire and pursuit of the whole is called love. There was a time, I say, when we were one, but now because of the wickedness of mankind we have been dispersed by the god, as the Arcadians were dispersed by the Spartans.[20] And if we are not obedient to the gods, there is a danger that we shall be split up again and go around looking like figures in a bas-relief, sliced in half down the line of our noses, like tallies. Wherefore let us exhort all men to piety, that we may avoid this fate, and obtain the other. So we take Eros as our guide and general. Let no one oppose him—he is the enemy of the gods who opposes him. For if we are friends of the god and at peace with him we shall find our own true boys, which happens to few people at present. “And please don't let Eryximachos suppose, in making a comedy of my speech, that it’s about Pausanias and Agathon, who, perhaps belong to this class, and are both males by nature. But my words have a wider application—they include men and women everywhere—this is where happiness for our race lies: in the successful pursuit of love, in finding the love who is part of our original self, and in returning to our ancient state. And if this would be best of all, the best in the next degree and under present circumstances must be the nearest approach to such an union; and that will be the attainment of a boyfriend whose nature is to one's taste. Wherefore, if we would praise him who has given to us the benefit, we must praise the Eros, who is our greatest benefactor, both leading us in this life back to our own, and giving us high hopes for the future, for he promises that if we are pious, he will restore us to our original state, and heal us and make us happy and blessed.  This, Eryximachos, is my discourse about Eros, which, although different to yours, I must beg you to leave unassailed by the shafts of your ridicule, in order that each may have his turn; each, or rather either, for Agathon and Sokrates are the only ones left. |

ἐπειδὴ οὖν ἡ φύσις δίχα ἐτμήθη, ποθοῦν ἕκαστον τὸ ἥμισυ τὸ αὑτοῦ συνῄει, καὶ περιβάλλοντες τὰς χεῖρας καὶ συμπλεκόμενοι ἀλλήλοις, [b] ἐπιθυμοῦντες συμφῦναι, ἀπέθνῃσκον ὑπὸ λιμοῦ καὶ τῆς ἄλλης ἀργίας διὰ τὸ μηδὲν ἐθέλειν χωρὶς ἀλλήλων ποιεῖν. καὶ ὁπότε τι ἀποθάνοι τῶν ἡμίσεων, τὸ δὲ λειφθείη, τὸ λειφθὲν ἄλλο ἐζήτει καὶ συνεπλέκετο, εἴτε γυναικὸς τῆς ὅλης ἐντύχοι ἡμίσει, ὃ δὴ νῦν γυναῖκα καλοῦμεν, εἴτε ἀνδρός· καὶ οὕτως ἀπώλλυντο. ἐλεήσας δὲ ὁ Ζεὺς ἄλλην μηχανην πορίζεται, καὶ μετατίθησιν αὐτῶν τὰ αἰδοῖα εἰς τὸ πρόσθεν· τέως γὰρ καὶ ταῦτα ἐκτὸς εἶχον, καὶ ἐγέννων καὶ ἔτικτον οὐκ εἰς ἀλλήλους ἀλλ᾿ εἰς γῆν, ὥσπερ οἱ τέττιγες· μετέθηκέ τε οὖν οὕτω ταῦτ᾿ αὐτῶν εἰς τὸ πρόσθεν [c] καὶ διὰ τούτων τὴν γένεσιν ἐν ἀλλήλοις ἐποίησε, διὰ τοῦ ἄρρενος ἐν τῷ θήλει, τῶνδε ἕνεκα, ἵνα ἐν τῇ συμπλοκῇ ἅμα μὲν εἰ ἀνὴρ γυναικὶ ἐντύχοι, γεννῷεν καὶ γίγνοιτο τὸ γένος, ἅμα δ᾿ εἰ καὶ ἄρρην ἄρρενι·, πλησμονὴ γοῦν γίγνοιτο τῆς συνουσίας καὶ διαπαύοιντο καὶ ἐπὶ τὰ ἔργα τρέποιντο καὶ τοῦ ἄλλου βίου ἐπιμελοῖντο.  ἔστι δὴ οὖν ἐκ τόσου [d] ὁ ἔρως ἔμφυτος ἀλλήλων τοῖς ἀνθρώποις καὶ τῆς ἀρχαίας φύσεως συναγωγεὺς καὶ ἐπιχειρῶν ποιῆσαι ἓν ἐκ δυοῖν καὶ ἰάσασθαι τὴν φύσιν τὴν ἀνθρωπίνην. Ἕκαστος οὖν ἡμῶν ἐστὶν ἀνθρώπου σύμβολον, ἅτε τετμημένος ὥσπερ αἱ ψῆτται, ἐξ ἑνὸς δύο. ζητεῖ δὴ ἀεὶ τὸ αὑτοῦ ἕκαστος σύμβολον. ὅσοι μὲν οὖν τῶν ἀνδρῶν τοῦ κοινοῦ τμῆμά εἰσιν, ὃ δὴ τότε ἀνδρόγυνον ἐκαλεῖτο, φιλογύναικές τ᾿ εἰσὶ καὶ οἱ πολλοὶ τῶν μοιχῶν ἐκ τούτου τοῦ γένους [e] γεγόνασι, καὶ ὅσαι αὖ γυναῖκες φίλανδροί τε καὶ μοιχεύτριαι, ἐκ τούτου τοῦ γένους γίγνονται. ὅσαι δὲ τῶν γυναικῶν γυναικὸς τμῆμά εἰσιν, οὐ πάνυ αὗται τοῖς ἀνδράσι τὸν νοῦν προσέχουσιν, ἀλλὰ μᾶλλον πρὸς τὰς γυναῖκας τετραμμέναι εἰσί, καὶ αἱ ἑταιρίστριαι ἐκ τούτου τοῦ γένους γίγνονται. ὅσοι δὲ ἄρρενος τμῆμά εἰσι, τὰ ἄρρενα διώκουσι, καὶ τέως μὲν ἂν παῖδες ὦσιν, ἅτε τεμάχια ὄντα τοῦ ἄρρενος, φιλοῦσι τοὺς ἄνδρας καὶ χαίρουσι [192a] συγκατακείμενοι καὶ συμπεπλεγμένοι τοῖς ἀνδράσι, καί εἰσιν οὗτοι βέλτιστοι τῶν παίδων καὶ μειρακίων, ἅτε ἀνδρειότατοι ὄντες φύσει. φασὶ δὲ δή τινες αὐτοὺς ἀναισχύντους εἶναι, ψευδόμενοι· οὐ γὰρ ὑπ᾿ ἀναισχυντίας τοῦτο δρῶσιν, ἀλλ᾿ ὑπὸ θάρρους καὶ ἀνδρείας καὶ ἀρρενωπίας, τὸ ὅμοιον αὐτοῖς ἀσπαζόμενοι. μέγα δὲ τεκμήριον· καὶ γὰρ τελεωθέντες μόνοι ἀποβαίνουσιν εἰς τὰ πολιτικὰ ἄνδρες οἱ τοιοῦτοι. ἐπειδὰν δὲ ἀνδρωθῶσι, [b] παιδεραστοῦσι καὶ πρὸς γάμους καὶ παιδοποιίας οὐ προσέχουσι τὸν νοῦν φύσει, ἀλλὰ ὑπὸ τοῦ νόμου ἀναγκάζονται· ἀλλ᾿ ἐξαρκεῖ αὐτοῖς μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων καταζῆν ἀγάμοις. πάντως μὲν οὖν ὁ τοιοῦτος παιδεραστής τε καὶ φιλεραστὴς γίγνεται, ἀεὶ τὸ συγγενὲς ἀσπαζόμενος. ὅταν μὲν οὖν καὶ αὐτῷ ἐκείνῳ ἐντύχῃ τῷ αὑτοῦ ἡμίσει καὶ ὁ παιδεραστὴς [c] καὶ ἄλλος πᾶς, τότε καὶ θαυμαστὰ ἐκπλήττονται φιλίᾳ τε καὶ οἰκειότητι καὶ ἔρωτι, οὐκ ἐθέλοντες, ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν, χωρίζεσθαι ἀλλήλων οὐδὲ σμικρὸν χρόνον. καὶ οἱ διατελοῦντες μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων διὰ βίου οὗτοί εἰσιν, οἳ οὐδ᾿ ἂν ἔχοιεν εἰπεῖν ὅ τι βούλονται σφίσι παρ᾿ ἀλλήλων γίγνεσθαι. οὐδενὶ γὰρ ἂν δόξειε τοῦτ᾿ εἶναι ἡ τῶν ἀφροδισίων συνουσία, ὡς ἄρα τούτου ἕνεκα ἕτερος ἑτέρῳ χαίρει συνὼν οὕτως ἐπὶ μεγάλης σπουδῆς· ἀλλ᾿ ἄλλο τι βουλομένη ἑκατέρου ἡ ψυχὴ δήλη ἐστίν, ὃ οὐ δύναται [d] εἰπεῖν, ἀλλὰ μαντεύεται ὃ βούλεται, καὶ αἰνίττεται. καὶ εἰ αὐτοῖς ἐν τῷ αὐτῷ κατακειμένοις ἐπιστὰς ὁ Ἥφαιστος, ἔχων τὰ ὄργανα, ἔροιτο· Τί ἔσθ᾿ ὃ βούλεσθε, ὦ ἄνθρωποι, ὑμῖν παρ᾿ ἀλλήλων γενέσθαι; καὶ εἰ ἀποροῦντας αὐτοὺς πάλιν ἔροιτο Ἆρά γε τοῦδε ἐπιθυμεῖτε, ἐν τῷ αὐτῷ γενέσθαι ὅτι μάλιστα ἀλλήλοις, ὥστε καὶ νύκτα καὶ ἡμέραν [e] μὴ ἀπολείπεσθαι ἀλλήλων; εἰ γὰρ τούτου ἐπιθυμεῖτε, ἐθέλω ὑμᾶς συντῆξαι καὶ συμφυσῆσαι εἰς τὸ αὐτό, ὥστε δύ᾿ ὄντας ἕνα γεγονέναι καὶ ἕως τ᾿ ἂν ζῆτε, ὡς ἕνα ὄντα, κοινῇ ἀμφοτέρους ζῆν, καὶ ἐπειδὰν ἀποθάνητε, ἐκεῖ αὖ ἐν Ἅιδου ἀντὶ δυοῖν ἕνα εἶναι κοινῇ τεθνεῶτε· ἀλλ᾿ ὁρᾶτε εἰ τούτου ἐρᾶτε καὶ ἐξαρκεῖ ὑμῖν ἂν τούτου τύχητε· ταῦτα ἀκούσας ἴσμεν ὅτι οὐδ᾿ ἂν εἷς ἐξαρνηθείη οὐδ᾿ ἄλλο τι ἂν φανείη βουλόμενος, ἀλλ᾿ ἀτεχνῶς οἴοιτ᾿ ἂν ἀκηκοέναι τοῦτο ὃ πάλαι ἄρα ἐπεθύμει, συνελθὼν καὶ συντακεὶς τῷ ἐρωμένῳ ἐκ δυοῖν εἷς γενέσθαι.  Τοῦτο γάρ ἐστι τὸ αἴτιον, ὅτι ἡ ἀρχαία φύσις ἡμῶν ἦν αὕτη καὶ ἦμεν ὅλοι· τοῦ ὅλου οὖν τῇ [193a] ἐπιθυμίᾳ καὶ διώξει ἔρως ὄνομα. καὶ πρὸ τοῦ, ὥσπερ λέγω, ἓν ἦμεν· νυνὶ δὲ διὰ τὴν ἀδικίαν διῳκίσθημεν ὑπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ, καθάπερ Ἀρκάδες ὑπὸ Λακεδαιμονίων. φόβος οὖν ἔστιν, ἐὰν μὴ κόσμιοι ὦμεν πρὸς τοὺς θεούς, ὅπως μὴ καὶ αὖθις διασχισθησόμεθα, καὶ περίιμεν ἔχοντες ὥσπερ οἱ ἐν ταῖς στήλαις καταγραφὴν ἐκτετυπωμένοι, διαπεπρισμένοι κατὰ τὰς ῥῖνας, γεγονότες ὥσπερ λίσπαι. ἀλλὰ τούτων ἕνεκα πάντ᾿ ἄνδρα χρὴ ἅπαντα παρακελεύεσθαι εὐσεβεῖν περὶ θεούς, ἵνα τὰ [b] μὲν ἐκφύγωμεν, τῶν δὲ τύχωμεν, ὡς ὁ Ἔρως ἡμῖν ἡγεμὼν καὶ στρατηγός. ᾧ μηδεὶς ἐναντία πραττέτω· πράττει δ᾿ ἐναντία, ὅστις θεοῖς ἀπεχθάνεται· φίλοι γὰρ γενόμενοι καὶ διαλλαγέντες τῷ θεῷ ἐξευρήσομέν τε καὶ ἐντευξόμεθα τοῖς παιδικοῖς τοῖς ἡμετέροις αὐτῶν, ὃ τῶν νῦν ὀλίγοι ποιοῦσι. καὶ μή μοι ὑπολάβῃ Ἐρυξίμαχος κωμῳδῶν τὸν λόγον, [c] ὡς Παυσανίαν καὶ Ἀγάθωνα λέγω· ἴσως μὲν γὰρ καὶ οὗτοι τούτων τυγχάνουσιν ὄντες καὶ εἰσὶν ἀμφότεροι τὴν φύσιν ἄρρενες· λέγω δὲ οὖν ἔγωγε καθ᾿ ἁπάντων καὶ ἀνδρῶν καὶ γυναικῶν, ὅτι οὕτως ἂν ἡμῶν τὸ γένος εὔδαιμον γένοιτο, εἰ ἐκτελέσαιμεν τὸν ἔρωτα καὶ τῶν παιδικῶν τῶν αὑτοῦ ἕκαστος τύχοι εἰς τὴν ἀρχαίαν ἀπελθὼν φύσιν. εἰ δὲ τοῦτο ἄριστον, ἀναγκαῖον καὶ τῶν νῦν παρόντων τὸ τούτου ἐγγυτάτω ἄριστον εἶναι· τοῦτο δ᾿ ἐστὶ παιδικῶν [d] τυχεῖν κατὰ νοῦν αὐτῷ πεφυκότων· οὗ δὴ τὸν αἴτιον θεὸν ὑμνοῦντες δικαίως ἂν ὑμνοῖμεν Ἔρωτα, ὃς ἔν τε τῷ παρόντι ἡμᾶς πλεῖστα ὀνίνησιν εἰς τὸ οἰκεῖον ἄγων, καὶ εἰς τὸ ἔπειτα ἐλπίδας μεγίστας παρέχεται, ἡμῶν παρεχομένων πρὸς θεοὺς εὐσέβειαν, καταστήσας ἡμᾶς εἰς τὴν ἀρχαίαν φύσιν καὶ ἰασάμενος μακαρίους καὶ εὐδαίμονας ποιῆσαι. Οὗτος, ἔφη, ὦ Ἐρυξίμαχε, ὁ ἐμὸς λόγος ἐστὶ περὶ Ἔρωτος, ἀλλοῖος ἢ ὁ σός. ὥσπερ οὖν ἐδεήθην σου, μὴ κωμῳδήσῃς αὐτόν, ἵνα καὶ τῶν λοιπῶν ἀκούσωμεν τί ἕκαστος ἐρεῖ, μᾶλλον δὲ τί Eἑκάτερος· Ἀγάθων γὰρ καὶ Σωκράτης λοιποί. |

Their host, the young dramatist Agathon then makes a poetic speech (194e-197e) praising Eros as the best and most beautiful of the gods. This provokes the philosopher Sokrates, who is treated by the others as pre-eminent in wisdom, to say that in his own speech he would only be willing to tell the truth about Eros (as opposed to simply praising him, according to the original plan), and then to begin it by questioning Agathon:

199e-212c

|

“And now,” said Sokrates, “I will ask about Eros:—Is Eros love of something or of nothing?” “Of something, surely,” Agathon replied. “Keep in mind this something of which you claim he is,” said Sokrates, “and tell me this—whether Eros desires this thing which he is love of.” “Yes, surely.” “And does he possess, or does he not possess, that which he loves and desires?” “Probably not, I should say.” “Think,” replied Sokrates, “I would have you consider whether 'necessarily' is not the word rather than probably. The inference that he who desires something is in want of something, and that he who desires nothing is in want of nothing, is in my judgment, Agathon, absolutely and necessarily true. What do you think?” “I agree with you.” “Very good. Would he who is great desire to be great, or he who is strong desire to be strong?” “That would be inconsistent with our previous admissions.” “For he cannot be in need of things he already has.” “Very true.” “And yet,” added Sokrates, “if a man being strong desired to be strong, or being swift desired to be swift, or being healthy desired to be healthy, in that case he might be thought to desire something which he already has or is. I give the example in order that we may avoid misconception. For the possessors of these qualities, Agathon, must be supposed to have their respective advantages at the time, whether they choose or not; and who can desire that which he has? Therefore, when a person says, I am well and wish to be well, or I am rich and wish to be rich, and I desire simply to have what I have—to him we shall reply: 'You, my friend, having wealth and health and strength, want to have the continuance of them; for at this moment, whether you choose or no, you have them. And when you say, I desire that which I have and nothing else, is not your meaning that you want to have what you now have in the future?' He must agree with us—must he not?” “He must,” replied Agathon.  “Then,” said Sokrates, “he desires that what he has at present may be preserved to him in the future, which is equivalent to saying that he desires something which is non-existent to him, and which as yet he has not got.” “Very true,” he said. “Then he and every one who desires, desires that which he has not already, and which is future and not present, and which he has not, and is not, and of which he is in want;—these are the sort of things which love and desire seek?” “Very true,” he said. “Then now,” said Sokrates, “let us recapitulate the argument. First, is not Eros love of something, and of something too which is wanting to a man?” “Yes,” he replied. “Remember further what you said in your speech, or if you do not remember I will remind you: you said that matters were arranged by the gods through love of the beautiful, for there could be no love of the ugly—did you not say something of that kind?” “Yes,” said Agathon. “Yes, my friend, and the remark was a just one. And if this is true, Love is the love of beauty and not of deformity?” He assented. “And the admission has been already made that Love is of something which a man wants and has not?” “Yes,” he said. “So Eros wants and does not have not beauty?” “That must be so”, he replied. “And would you call that beautiful which wants and does not possess beauty?” “Certainly not.” “Then would you still say that Eros is beautiful?” Agathon replied: “I fear, Sokrates, that I did not understand what I was saying.” “You made a very good speech, Agathon,” he replied; but there is yet one small question which I would fain ask:—Is not the good also the beautiful?” “Yes.” “Then in wanting the beautiful, Eros wants also the good?” “I cannot refute you, Sokrates. Let us assume that what you say is true.” “Say rather, dear Agathon, that you cannot refute the truth; for Sokrates is easily refuted.”  “And now, I shall let you alone, as I would turn to a discourse on Eros which I heard from Diotima[21] of Mantineia, a woman wise in this and in many other subjects, who in the days of old, when the Athenians offered sacrifice before the coming of the plague, caused the onset of the disease to be delayed ten years.[22] She taught me about love, and I shall try to tell you as best I can what she said to me, starting from the position on which Agathon and I reached agreement, which is nearly if not quite the same which I made to the wise woman when she questioned me: I think that this will be the easiest way, and I shall take both parts myself as well as I can. As you, Agathon, explained, one must first say who Eros is and what he is like, and then of his deeds. First I said to her in nearly the same words which Agathon used to me, that Eros was a mighty god, and was the love of beauty. She proved to me as I proved to him that, by my own argument, Eros was neither beautiful nor good. |

Πειρῶ δή, φάναι, καὶ τὸν ἔρωτα εἰπεῖν. ὁ Ἔρως ἔρως ἐστιν οὐδενὸς ἢ τινός; [200a] Πάνυ μὲν οὖν ἔστιν. Τοῦτο μὲν τοίνυν, εἰπεῖν τὸν Σωκράτη, φύλαξον παρὰ σαυτῷ μεμνημένος ὅτου· τοσόνδε δὲ εἰπέ, πότερον ὁ Ἔρως ἐκείνου, οὗ ἔστιν ἔρως, ἐπιθυμεῖ αὐτοῦ ἢ οὔ; Πάνυ γε, φάναι. Πότερον ἔχων αὐτὸ οὗ ἐπιθυμεῖ τε καὶ ἐρᾷ, εἶτα ἐπιθυμεῖ τε καὶ ἐρᾷ, ἢ οὐκ ἔχων; Οὐκ ἔχων, ὡς τὸ εἰκός γε, φάναι. Σκόπει δή, εἰπεῖν τὸν Σωκράτη, ἀντὶ τοῦ εἰκότος [b] εἰ ἀνάγκη οὕτως, τὸ ἐπιθυμοῦν ἐπιθυμεῖν οὗ ἐνδεές ἐστιν, ἢ μὴ ἐπιθυμεῖν, ἐὰν μὴ ἐνδεὲς ᾖ; ἐμοὶ μὲν γὰρ θαυμαστῶς δοκεῖ, ὦ Ἀγάθων, ὡς ἀνάγκη εἶναι· σοὶ δὲ πῶς; Κἀμοί, φάναι, δοκεῖ. Καλῶς λέγεις. ἆρ᾿ οὖν βούλοιτ᾿ ἄν τις μέγας ὢν μέγας εἶναι, ἢ ἰσχυρὸς ὢν ἰσχυρός; Ἀδύνατον ἐκ τῶν ὡμολογημένων. Οὐ γάρ που ἐνδεὴς ἂν εἴη τούτων ὅ γε ὤν. Ἀληθῆ λέγεις. Εἰ γὰρ καὶ ἰσχυρὸς ὢν βούλοιτο ἰσχυρὸς εἶναι, φάναι τὸν Σωκράτη, καὶ ταχὺς ὢν ταχύς, καὶ ὑγιὴς ὢν ὑγιής—ἴσως γὰρ ἄν τις ταῦτα οἰηθείη [c] καὶ πάντα τὰ τοιαῦτα, τοὺς ὄντας τε τοιούτους καὶ ἔχοντας ταῦτα τούτων ἅπερ ἔχουσι καὶ ἐπιθυμεῖν, ἵν᾿ οὖν μὴ ἐξαπατηθῶμεν, τούτου ἕνεκα λέγω—τούτοις γάρ, ὦ Ἀγάθων, εἰ ἐννοεῖς, ἔχειν μὲν ἕκαστα τούτων ἐν τῷ παρόντι ἀνάγκη ἃ ἔχουσιν, ἐάν τε βούλωνται ἐάν τε μή, καὶ τούτου γε δήπου τίς ἂν ἐπιθυμήσειεν; ἀλλ᾿ ὅταν τις λέγῃ ὅτι ἐγὼ ὑγιαίνων βούλομαι καὶ ὑγιαίνειν, καὶ πλουτῶν βούλομαι καὶ πλουτεῖν, καὶ ἐπιθυμῶ αὐτῶν τούτων ἃ ἔχω, εἴποιμεν ἂν αὐτῷ ὅτι σύ, [d] ὦ ἄνθρωπε, πλοῦτον κεκτημένος καὶ ὑγίειαν καὶ ἰσχὺν βούλει καὶ εἰς τὸν ἔπειτα χρόνον ταῦτα κεκτῆσθαι, ἐπεὶ ἐν τῷ γε νῦν παρόντι, εἴτε βούλει εἴτε μή, ἔχεις· σκόπει οὖν, ὅταν τοῦτο λέγῃς, ὅτι ἐπιθυμῶ τῶν παρόντων, εἰ ἄλλο τι λέγεις ἢ τόδε, ὅτι βούλομαι τὰ νῦν παρόντα καὶ εἰς τὸν ἔπειτα χρόνον παρεῖναι· ἄλλο τι ὁμολογοῖ ἄν; Συμφάναι ἔφη τὸν Ἀγάθωνα. Εἰπεῖν δὴ τὸν Σωκράτη, Οὐκοῦν τοῦτό γ᾿ ἐστὶν ἐκείνου ἐρᾶν, ὃ οὔπω ἕτοιμον αὐτῷ ἐστὶν οὐδὲ ἔχει, τὸ εἰς τὸν ἔπειτα χρόνον ταῦτα εἶναι αὐτῷ σῳζόμενα καὶ ἀεὶ1 παρόντα; Πάνυ γε, φάναι. [e] Καὶ οὗτος ἄρα καὶ ἄλλος πᾶς ὁ ἐπιθυμῶν τοῦ μὴ ἑτοίμου ἐπιθυμεῖ καὶ τοῦ μὴ παρόντος, καὶ ὃ μὴ ἔχει καὶ ὃ μὴ ἔστιν αὐτὸς καὶ οὗ ἐνδεής ἐστι, τοιαῦτ᾿ ἄττα ἐστὶν ὧν ἡ ἐπιθυμία τε καὶ ὁ ἔρως ἐστίν; Πάνυ γ᾿, εἰπεῖν. Ἴθι δή, φάναι τὸν Σωκράτη, ἀνομολογησώμεθα τὰ εἰρημένα. ἄλλο τι ἔστιν ὁ Ἔρως πρῶτον μὲν τινῶν, ἔπειτα τούτων ὧν ἂν ἔνδεια παρῇ αὐτῷ; Ναί, φάναι.  [201a] Ἐπὶ δὴ τούτοις ἀναμνήσθητι τίνων ἔφησθα ἐν τῷ λόγῳ εἶναι τὸν Ἔρωτα· εἰ δὲ βούλει, ἐγώ σε ἀναμνήσω. οἶμαι γάρ σε οὑτωσί πως εἰπεῖν, ὅτι τοῖς θεοῖς κατεσκευάσθη τὰ πράγματα δι᾿ ἔρωτα καλῶν· αἰσχρῶν γάρ οὐκ εἴη ἔρως. οὐχ οὑτωσί πως ἔλεγες; Εἶπον γάρ, φάναι τὸν Ἀγάθωνα. Καὶ ἐπιεικῶς γε λέγεις, ὦ ἑταῖρε, φάναι τὸν Σωκράτη· καὶ εἰ τοῦτο οὕτως ἔχει, ἄλλο τι ὁ Ἔρως κάλλους ἂν εἴη ἔρως, αἴσχους δ᾿ οὔ; Ὡμολόγει. [b] Οὐκοῦν ὡμολόγηται, οὗ ἐνδεής ἐστι καὶ μὴ ἔχει, τούτου ἐρᾶν; Ναί, εἰπεῖν. Ἐνδεὴς ἄρ᾿ ἐστὶ καὶ οὐκ ἔχει ὁ Ἔρως κάλλος. Ἀνάγκη, φάναι. Τί δέ; τὸ ἐνδεὲς κάλλους καὶ μηδαμῇ κεκτημένον κάλλος ἆρα λέγεις σὺ καλὸν εἶναι; Οὐ δῆτα. Ἔτι οὖν ὁμολογεῖς Ἔρωτα καλὸν εἶναι, εἰ ταῦτα οὕτως ἔχει; Καὶ τὸν Ἀγάθωνα εἰπεῖν Κινδυνεύω, ὦ Σώκρατες, οὐδὲν εἰδέναι ὧν τότε εἶπον. [c] Καὶ μὴν καλῶς γε εἶπες, φάναι, ὦ Ἀγάθων. ἀλλὰ σμικρὸν ἔτι εἰπέ· τἀγαθὰ οὐ καὶ καλὰ δοκεῖ σοι εἶναι; Ἔμοιγε. Εἰ ἄρα ὁ Ἔρως τῶν καλῶν ἐνδεής ἐστι, τὰ δὲ ἀγαθὰ καλά, κἂν τῶν ἀγαθῶν ἐνδεὴς εἴη. Ἐγώ, φάναι, ὦ Σώκρατες, σοὶ οὐκ ἂν δυναίμην ἀντιλέγειν, ἀλλ᾿ οὕτως ἐχέτω ὡς σὺ λέγεις. Οὐ μὲν οὖν τῇ ἀληθείᾳ, φάναι, ὦ φιλούμενε [d] Ἀγάθων, δύνασαι ἀντιλέγειν, ἐπεὶ Σωκράτει γε οὐδὲν χαλεπόν. Καὶ σὲ μέν γε ἤδη ἐάσω· τὸν δὲ λόγον τὸν περὶ τοῦ Ἔρωτος, ὅν ποτ᾿ ἤκουσα γυναικὸς Μαντινικῆς Διοτίμας, ἣ ταῦτά τε σοφὴ ἦν καὶ ἄλλα πολλά, καὶ Ἀθηναίοις ποτὲ θυσαμένοις πρὸ τοῦ λοιμοῦ δέκα ἔτη ἀναβολὴν ἐποίησε τῆς νόσου, ἣ δὴ καὶ ἐμὲ τὰ ἐρωτικὰ ἐδίδαξεν—ὃν οὖν ἐκείνη ἔλεγε λόγον, πειράσομαι ὑμῖν διελθεῖν ἐκ τῶν ὡμολογημένων ἐμοὶ καὶ Ἀγάθωνι, αὐτὸς ἐπ᾿ ἐμαυτοῦ, ὅπως ἂν δύνωμαι. δεῖ δή, ὦ Ἀγάθων, [e] ὥσπερ σὺ διηγήσω, διελθεῖν αὐτὸν πρῶτον, τίς ἐστιν ὁ Ἔρως καὶ ποῖός τις, ἔπειτα τὰ ἔργα αὐτοῦ. δοκεῖ οὖν μοι ῥᾷστον εἶναι οὕτω διελθεῖν, ὥς ποτέ με ἡ ξένη ἀνακρίνουσα διῄει. σχεδὸν γάρ τι καὶ ἐγὼ πρὸς αὐτὴν ἕτερα τοιαῦτα ἔλεγον, οἷάπερ νῦν πρὸς ἐμὲ Ἀγάθων, ὡς εἴη ὁ Ἔρως μέγας θεός, εἴη δὲ τῶν καλῶν· ἤλεγχε δή με τούτοις τοῖς λόγοις οἷσπερ ἐγὼ τοῦτον, ὡς οὔτε καλὸς εἴη κατὰ τὸν ἐμὸν λόγον οὔτε ἀγαθός. |

|

“'What do you mean, Diotima,' I said, 'is love then ugly and bad?' “'Hush,' she cried; 'must that be ugly which is not beautiful?' “'Certainly,' I said. “'And is that which is not wise, ignorant? Don’t you see that there is something in between wisdom and ignorance?' “'And what may that be?' I said. “’Don’t you know that correct opinion for which a reason cannot be given is not knowledge (for how can knowledge be devoid of reason?) nor is it ignorance (for neither can ignorance attain the truth), but is clearly something in between ignorance and wisdom.' “'Quite true,' I replied. “'Do not then insist that what is not beautiful is necessarily ugly, or what is not good bad; or infer that, because Eros is not good or beautiful, he is therefore ugly and bad; for he is something in between them.' “'And yet,' I said, 'he is surely admitted by all to be a great god.' “'By those who know or by those who do not know?' “'By all.' “'And how, Sokrates,' she said with a laugh, 'can Eros be acknowledged to be a great god by those who say that he is not a god at all?' “'And who are they?' I said. “You are one and I am one,' she replied. “'How can that be?' I said. “'It is quite intelligible,' she replied; 'for you yourself would acknowledge that the gods are happy and beautiful—of course you would—would you dare to say that any god was not?' “'Certainly not,' I replied. “'And you mean by the happy, those who are the possessors of things good or beautiful?' “'Yes.' “'And you admitted that Eros, because he was in want, desires those good and beautiful things of which he is in want?' “'Yes, I did.' “'But how can he be a god who has no portion in what is either beautiful and good?' “'Impossible.' “'Then you see that you also deny the divinity of Eros.' “'What then is Eros?' I asked; 'Is he mortal?' “'No.' “'What then?' “'As in the former instance, he is neither mortal nor immortal, but in between.'  “'What is that, Diotima?' “’A great spirit,’ Sokrates ‘and like all spirits he is intermediate between the divine and the mortal.' “'And what,' I said, 'is his power?' “'He interprets and communicates between gods and men, taking across to the gods the requests and sacrifices of men, and bringing back to men the commands and replies of the gods He is the mediator who spans the chasm which divides them, and therefore in him all is bound together, and through him the arts of the prophet and the priest, their sacrifices and mysteries and charms, and all prophecy and magic, find their way. For there is no mingling between god and man; but through Eros all intercourse and conversation between them, whether awake or asleep, is carried on. Wisdom of this kind is spiritual; all other wisdom, such as that of arts and handicrafts, is mean and vulgar. Now these spirits are many and diverse, and one of them is Eros.' “'And who,' I said, 'was his father, and who his mother?' “'The tale,' she said, 'will take time; nevertheless I will tell you. When Aphrodite was born, there was a feast of the gods, at which the god Poros or Plenty, who is the son of Metis or Discretion, was one of the guests. When the feast was over, Penia or Poverty, as the manner is on such occasions, came about the doors to beg. Now Plenty who was drunk on nectar (there was no wine in those days), went into the garden of Zeus and fell into a heavy sleep. Then Poverty considering her own straitened circumstances, plotted to have a child by him, and accordingly she lay down at his side and conceived Eros, who partly because he is naturally a lover of the beautiful, and because Aphrodite is herself beautiful, and also because he was born on her birthday, is her follower and attendant. “’So Eros’ attributes are what you would expect of a child of Resource and Poverty. In the first place he is always poor, and anything but tender and beautiful, as the many imagine him; and he is rough and squalid, and has no shoes, nor a house to dwell in; on the bare earth exposed he lies under the open heaven, in the streets, or at the doors of houses, taking his rest; and like his mother he is always in need. Like his father too, whom he also partly resembles, he is always plotting against the beautiful and good; he is bold, enterprising, strong, a skilled hunter, always weaving some intrigue or other, keen in the pursuit of wisdom, fertile in resources; a philosopher at all times, terrible as an enchanter, sorcerer, sophist. He is by nature neither mortal nor immortal, but alive and flourishing at one moment when he is in plenty, and dead at another moment, and again alive by reason of his father's nature. But that which is always flowing in is always flowing out, and so he is never in want and never in wealth; and, further, he is in a mean between wisdom and folly. The truth of the matter is this: No god is a philosopher or seeker after wisdom, for he is wise already; nor does any man who is wise seek after wisdom. Neither do the foolish seek after wisdom, since folly is precisely the failing which consistes is not being beautiful or good or intelligent and nevertheless being satisfied with oneself. One cannot desire what one does not know one lacks.’  “'But who then, Diotima,' I said, 'are the lovers of wisdom, if they are neither the wise nor the foolish?' “'A child may answer that question,' she replied; 'they are those who are between the two, of whom Eros is one. For wisdom is a most beautiful thing, and Eros is love of the beautiful; and therefore Eros is necessarily a lover of wisdom, and being a lover of wisdom is in a mean between the wise and the foolish. And of this too his birth is the cause; for his father is wealthy and wise, and his mother poor and foolish. Such, my dear Sokrates, is the nature of this spirit. The error in your conception of him was very natural, and as I imagine from what you say, has arisen out of a confusion of love and the beloved, which made you think that Eros was what was loved, rather than the lover. For the beloved is the truly beautiful, and delicate, and perfect, and blessed; but the lover is of another nature, and is such as I have described.' “And I said, 'All right,’ stranger, ‘what you say is fine. But, assuming Eros to be such as you say, what is the use of him to men?' “'That, Sokrates,' she replied, 'I will attempt to unfold: of his nature and birth I have already spoken; and you acknowledge that Eros is of the beautiful. But some one will ask: Of the beautiful in what, Sokrates and Diotima?—or rather let me put the question more clearly, and ask: When a man loves the beautiful, what does he desire?' “I answered her 'That the beautiful may be his.' “'Still,' she said, 'the answer suggests a further question: What is given by the possession of beauty?' “'To what you have asked,' I replied, 'I have no answer ready.' “'Then,' she said, 'let me put the word "good" in the place of the beautiful, and repeat the question once more: If he who loves loves the good, what is it then that he loves?' “'The possession of the good,' I said. “'And what does he gain who possesses the good?' “'Happiness,' I replied; 'there is less difficulty in answering that question.' “'Yes,' she said, 'the happy are made happy by the acquisition of good things. Nor is there any need to ask why a man desires happiness; the answer is already final.' “'You are right.' I said. “'And is this wish and this desire common to all, and do all men always desire to possess what is good, or only some men? What say you?' “'All men,' I replied; 'the desire is common to all.' “'Why, then,' she rejoined, 'are not all men, Socrates, said to love, but only some of them, if everyone is always loving the same things.' Why do we say that some love and some do not?' “'I myself wonder,' I said, 'why this is.' “'There is nothing to wonder at,' she replied; 'the reason is that one part of love is separated off and receives the name of the whole, but the other parts have other names.' “'Give an illustration,' I said.  “'What about this? Take a concept like “making”. Every kind of making is responsible for anything whatsoever that is on the way from what is not to what is. And thus all the productions that are dependent on the arts are makings, and all the craftsmen engaged in them are makers.' “'Very true.' “'Still,' she said, 'you know that not all craftsmen are called makers, and one part is separated off from all of making—that which is concerned with music and metre—and is addressed by the name of the whole. For this alone is called poetry; and those who have this part of making are poets.' “'Very true,' I said. “'And the same holds of love. For you may say generally that all desire for good things and happiness is Eros, and it is a great and subtle force; but they who are drawn towards him by any other path, whether the path of money-making or gymnastics or philosophy, are not called lovers—the name of the whole is appropriated to those whose affection takes one form only—they alone are said to love, or to be lovers.' “'I dare say,' I replied, 'that you are right.' 'And,' she added, 'you hear people say that lovers are seeking for their other half; but I say that love is not love of a half, nor of a whole, unless it is good. And men will cut off their own hands and feet and cast them away, if they are no good. For they love not what is their own, except in so far as they regard what belongs to them as good, and what belongs to others as evil. For there is nothing which men love other than the good, will you not agree?' "‘Yes, I certainly agree.’ “'Then,' she said, 'the simple truth is, that men love the good.' “'Yes,' I said. “'To which must be added that they love the possession of the good?' “'Yes, that must be added.' “'And not only the possession, but the everlasting possession of the good?' “'That must be added too.' “'Then love,' she said, 'may be described generally as the love of the everlasting possession of the good?' “'That is most true.' “'Then if this be the nature of love,' she said, 'what is the manner of pursuit, and what is the activity, in which enthusiasm and effort is called love? What in fact are they doing when they act so? Can you tell?' “'Nay, Diotima,' I replied, 'if I had known, I should not have wondered at your wisdom, neither should I have come to learn from you about this very matter.' “'Well,' she said, 'I will tell you:—The object which they have in view is birth in beauty, whether of body or soul.' “'I do not understand you,' I said; 'the oracle requires an explanation.'  “'I will make my meaning clearer,' she replied. 'Reproduction, Socrates, both of body and soul, is a universal human activity. There is a certain age at which human nature is desirous of procreation, but it is incapable of giving birth in ugliness, and insists on what is beautiful. This procreation is the union of man and woman, and is a divine thing; for conception and generation are an immortal principle in the mortal creature. In the unfitting they can never be, and the ugly is unfitting with everything divine, but the beautiful is fitting. Beauty, then, is the destiny or goddess of parturition who presides at birth, which is why the urge to reproduce becomes gentle and happy when it comes near beauty: then conception and begetting become possible. But, at the sight of ugliness she frowns and contracts and has a sense of pain, and turns away, and shrivels up, and not without a pang refrains from conception. And this is the reason why, when the hour of conception arrives, and the teeming nature is full, there is such a flutter and ecstasy about beauty whose approach is the alleviation of the pain of reproduction. For love, Socrates, is not, as you imagine, the love of the beautiful.' “'What then?' "‘It is the desire to use beauty to beget and bear offspring.’ “'Yes,' I said. “'Yes, indeed,' she replied. 'But why to beget?' 'Because to the mortal creature, begetting is a sort of eternity and immortality, and if, as has been already admitted, love is the desire for everlasting possession of the good, all men will necessarily desire immortality together with good: Wherefore love must be desire for immortality too.' |