A REVIEW OF THE FILM WHOLE NEW THING (2005)

Whole New Thing is a Canadian drama directed by Amnon Buchbinder. It stars Aaron Webber, Daniel MacIvor, Robert Joy and Rebecca Jenkins, and runs 92 min.

An Incomplete Something or Other

by Sam Hall, 13 June 2022

I defy anyone to love or hate this movie. It manages to irritate at times, but not to any great issue. None of the characters are overly interesting or likable, the occasional worthy idea is floated only to be sent gently on its way unmolested, and the climax ties a cleverish bow on a big bowl of not much. A fair to middling thing is the Whole New Thing.

The central premise is promising. What happens when a thirteen-year-old boy, home-schooled, raised to be uninhibited about sex and nudity -- what happens when he reaches puberty? Aaron Webber's performance as Emerson Thorsen is generally lauded as excellent, although this seems based mainly on his androgynous looks. It's true Webber looks like a long-haired Harry Potter the cat dragged in, but he's sixteen when playing this thirteen-year-old, and while that isn't necessarily a deal-breaker, in this case I think it lies behind the unconvincing emotional content of the character. The fact is that it's extremely rare, if not completely unknown, to find a child actor with the range and control of an experienced adult. It's likely an unmitigable physiological barrier. What's required is a more careful tailoring of the script to the boy-in-himself. It simply hasn't worked here. But the fact that Emerson remains the film's most engaging character does speak volumes.

The Thorsen family -- Kaya and Rog and their son Emerson -- have built a green dream getaway out on their own in the freezing wilds of Nova Scotia. Although they have a solid friendship circle they regularly see, the nuclear family is not thriving. Rog's career ambition of turning human excrement into something tasty has dwindled almost as low as his now non-existent sex life. Kaya, made restless by an eco-fantasia full of male ineptitude, seeks a lover for herself and sends her dreamy innumerate son to high school. Perhaps he needs to toughen up a bit, she heretically suggests, causing a shocked Rog to pale a little further.

The film kicks off with Emerson attaining spermache, waking up to the results of his first wet dream. Mum is right there at the changing of the sheets to enthuse over what a wonderful event this is, and nothing to be ashamed of, etc. Well, yes, but only up to a point, Mum. Dad also wants in on the action, ready and willing to discuss the stickier details. We've seen how comfortable Emerson is with full nudity around his parents and it appears perfectly natural and good. But the boy does resist, equally naturally, the parental attempt to claim his new ejaculatory achievement as another joyous entry in the family scrapbook. A similar new breach appears in Emerson's talent for massage. A female family friend, used to the boy giving her wonderful back rubs, suddenly finds Emerson breaking off mid-massage and rushing from the room due to an unruly erection. The time-honoured dividing line has been reached. Puberty rites at this age put a boy through an ordeal of some kind in order to then place him in a new, sexually awakened role within his community. Full sexual maturity is of course still a long way off, but, biologically, it's not as distant as his now former childhood.

Emerson's newly acquired talent for ejaculation brings with it a need to eject himself from the warm scrotal safety of his eco-friendly home. It's a life-principle traversing the five kingdoms: Have seed, must travel. The local high school is the scene of Emerson's daring life-launch and his English teacher, Don Grant, becomes the specific first-up target. The relationship between the boy and his teacher is central and, typically for this film, things get off to a promising start before fading into the lacklustre.

The two first meet when lonely, awkward, middle-aged Don Grant arrives at the Thorsen's for dinner. He chats to the two parents with nervous difficulty, then shifts a gear as he engages Emerson in conversation, suddenly showing some wit and verve and even getting a glimmer of a smile from the far-away boy. Curiously, that's all we get as far as any chemistry goes between them. On paper the plot makes sense: boy finds man an engaging teacher of a subject he loves (literature) and, with dizzying new ideas and possibilities aswirl in his rapidly expanding universe, he falls in love. Somehow, though, this never quite makes it onto the screen as a three-dimensional reality.

It shouldn't have mattered that Mr. Grant was an openly gay man. Although perhaps the political sensitivities this unavoidably drags in interfered with the basic man-to-boy requirements of the role. Modern politics is, after all, increasingly post-human in its aspirations. Grant's feelings for the boy never get much beyond those of an honest, plodding bureaucrat nervously trying to negotiate a particularly tricky human resource issue. So the boy's rush of sonnet-penning love becomes a rather bizarre solo affair. These two character states are the respective square one's from which the two main characters were meant to grow. It didn't happen. If anything, they became more entrenched in their original flawed state until the very last moment and the tricky, unsatisfying ta-da ending.

Perhaps the bringing together of this man and this boy was from the start a doomed artistic exercise. Emerson has been raised without body-shame or sex-phobia so his belief that a sexual relationship with Mr. Grant would be as natural and good as the winter is cold and cruel, seems a logic hard to refute. Grant, though, is a gay man, so he can't, in good faith, feel any genuine sexual attraction to a thirteen-year-old boy. But he does have to "care" for the boy a great deal, otherwise the Whole New Thing will end up a whole lot of nothing. But this "care" is so generic, scattered and shallow, the film limps at its self-inflicted wound the whole way through.

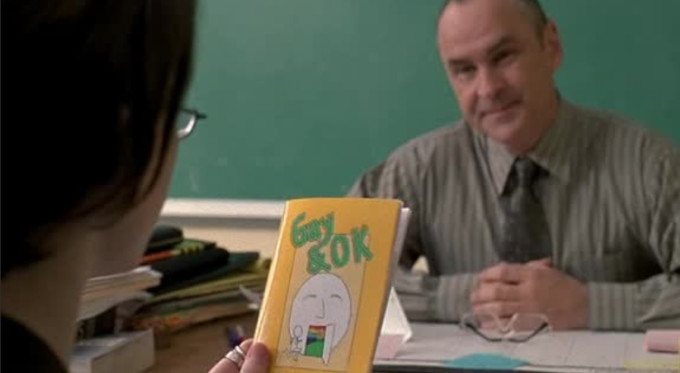

The literary connection between the man and boy was another theme that promised to deploy a friendship depth-charge or two, but instead fizzled disappointingly. In an early important scene, where Emerson's falling for his teacher is made explicit, Mr. Grant is competently explaining the difference between comedy and tragedy. As Emerson's interest is strongly roused, Mr. Grant inexplicably drifts off into a melancholic reverie of his own rather sad life. Goodbye Mister Soggy Spuds. And when Mr. Grant comes to give his opinion on Emerson's recently penned novel -- he is the only person allowed to read it -- he offers the most trite well-done before again seguing into a glum reminiscence on his failed love life. The boy has to be commended on his imagination in being able to keep this so-called budding romance afloat. What was offered this drab, disappointed middle-aged man was a chance to man up in a traditional, useful, exciting, dangerous and honourable way. He never got close.

But the literary connection does throw up one of the film's treasured bits of symbolic commentary, one that provides a useful diagnostic tool in getting to the root cause of this film's fatal listlessness. Emerson decries the classroom set text and succeeds in inspiring Mr. Grant to throw it out in favour of Shakespeare's As You Like It. Ah, yes, delicious: Emerson as Rosalind -- precocious wit and social catalyst in the shapeshifting form of a bold androgyne. A boy plays a girl playing a boy -- a frisson felt around the globe! Of course Shakespeare didn't realise that Rosalind's greatest need was to be locked up and kept safe from the horrific dangers of her own high spiritedness, but perfection in moral matters was still four hundred years away.

But the literary connection does throw up one of the film's treasured bits of symbolic commentary, one that provides a useful diagnostic tool in getting to the root cause of this film's fatal listlessness. Emerson decries the classroom set text and succeeds in inspiring Mr. Grant to throw it out in favour of Shakespeare's As You Like It. Ah, yes, delicious: Emerson as Rosalind -- precocious wit and social catalyst in the shapeshifting form of a bold androgyne. A boy plays a girl playing a boy -- a frisson felt around the globe! Of course Shakespeare didn't realise that Rosalind's greatest need was to be locked up and kept safe from the horrific dangers of her own high spiritedness, but perfection in moral matters was still four hundred years away.

The prominence of As You Like It throws the wrongheadedness of the ending into sharper relief. Whole New Thing is a comedy where love and marriage, after much tumult, win the day. And Emerson as Rosalind is the instigator of both the tumult and the love-conquers-all finale. His dogged pursuit of Mr. Grant is the catalyst for the formation of two love-matches: it brings his separated mum and dad back together, and it prods Mr. Grant into daring to give love a chance -- not with the deserving hero of our story, as was Rosalind's happy fate, but with some other random middle-aged dude hurriedly introduced in the run home -- some old flame or Pete Buttigieg's better half or a butler or something. Moving stuff. It would be more accurate to propose As You Like It's Jaques as Emerson's Shakespearean counterpart. He's the one character who ends up alone, preferring a cave of nihilistic, melancholic solitude to any of the silly love nonsense going on. Emerson's only thirteen, so he needs some determined help to be convinced of the cave's desirability; fortunately there are plenty of knowing adults on hand to help with this.

Emerson's removal from his own love story is carried out clinically and predictably. As he approaches dangerously close to his desired first-love relationship, a pedo stereotype leaps from the bushes to save us all from sin. A man cruising for some young-but-legal rent-boy action picks up Emerson, who is determined to punish Mr. Grant for preferring anonymous beat sex to himself (for a dreamer, the boy does have a habit of acting with disarming rationality). Once the man discovers the boy is in fact only thirteen and in emotional distress, he of course turns aggressive, quickly and angrily discarding a sex toy that turned out to be defective. The horror of pederastic sex has been firmly driven home -- before discovering the boy is not legal, we are given an extended lurid hint of some real creepy shit, man. Anyway, the upshot is that a distraught Emerson, after escape, is free to be wafted back to the family couch where he falls asleep under the loving protection of his close-hovering parents. Love and happiness for all, except for the boy-hero, who instead becomes a loving sacrifice to Safety -- one which makes the angelic intervention to save Abraham's son look lily-livered.

Calling this a rites of passage film is like treating Weekend at Bernies as a serious meditation on mortality. In terms of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, the new knowledge gained by the protagonist's adventure turns out to be that he must not and cannot pursue any sexual knowledge or experience outside his own carefully laundered cocoon. His wet dream turns out to have been a succubus, tempting him to pursue a forbidden and dangerous evil. A good boy-hero stays home and cheerfully accepts his mum's congratulations on the safe, solo, sticky ticking by of years. Emerson's father Rog confirms this with the film's last line. Gazing upon his sleeping son, he declares, with revelatory wonder, that he has no idea what his boy is dreaming about. Earlier, Rog had given the odd advice that his son should masturbate more to cut down on the wet dreams. Now we know why. Let a boy dream without inhibition and who knows what sort of outrages on life and love he might attempt.

Comments

If you would like to leave a comment on this webpage, please e-mail it to greek.love.tta@gmail.com, mentioning either the title or the url of the page so that the editor can add it. You could also indicate the name by which you wish to be known.